LiDAR’s Role in Assessing Facility Conditions

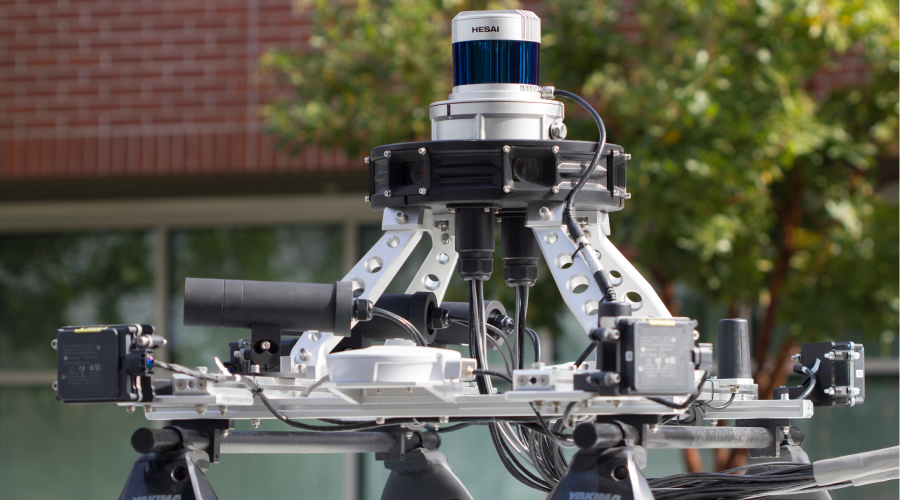

Light detection and ranging captures information on facility components, including walls, ceilings, roofs, stairs and risers for advanced site models.

By Robert Hendricks, Contributing Writer

For building owners and managers who are looking to purchase or sell properties, renovate existing sites, have experienced a catastrophic event or just have noticed troubling anomalies like surface cracks or uneven flooring, a relative floor elevation (RFE) model and its analysis delivers valuable information.

Reducing floor variation is essential to reducing wear and tear on the surface, on machinery and to the safe application of self-guided equipment. Light detection and ranging (LiDAR) technology has emerged as the methodology of choice to assess a facility’s condition, so it is essential to understand it and how it compares to traditional, analog methodologies of evaluating facility condition.

LiDAR: A closer look

LiDAR is an active remote-sensing method that measures the two-way travel time of a laser pulse. The line-of-sight tool can measure the distance to any surface visible to the machine by collecting millions of data points from targeted surfaces and organizing them into one data set, often referred to as a point cloud. LiDAR also can generate high-resolution photography by adding an RGB color field to each point collected.

Terrestrial, or ground-based, LiDAR is typically performed using a unit on a tripod. The unit scans its surroundings and then is moved to another position to ensure overlap between each of the scan sites. The scans are compiled to create a complete point cloud of the site.

Floor surfaces designed to be flat or gently sloped often consist of minute topographic changes. Detecting these changes requires measurements to one-eighth of an inch, essential for creating RFEs to support forensic building investigations. This level of accuracy is not readily achievable with global positioning systems (GPS) or similar systems in an interior space. Partition walls, stored materials and furniture also create challenges in the collection of elevation data.

The traditional analog tool most often used to create RFEs is a fluid level, which uses changes in the level of an internal fluid to measure variations in elevation. This method presents unavoidable procedural issues that diminish the quality of the RFE data.

The primary limitation is that the device requires elevation measurements to be collected at discrete locations. The selection of each measurement location is decided by the operator, who depends on provided site drawings. A typical RFE collected using this method might include a few dozen to a few hundred data points, depending on the size of the space, obstructions present and the skill and will of the operator.

The data points also might be spaced between a few feet to tens of feet apart, limiting the ability of this method to resolve small-scale features such as isolated depressions or cracks. This means of locating elevation measurements introduces several elements of human bias into the collection process:

Points near areas of visually obvious distress might be collected over data near areas that are visually undisturbed, resulting in an RFE that is biased toward a distressed outcome, which might not represent site conditions.

The method of determining a measurement’s location relies on the operator’s ability to accurately locate themselves within the building and the building drawing’s accuracy.

Another challenge operators can encounter when using a fluid level to create RFEs involves changes in temperature during the survey, which can cause the fluid to expand or contract and result in variations of the recorded elevation data that are unrelated to topographic changes.

Once collected, the operator needs to convert fluid level measurements into a digital spatial database for analysis. To process this data, the operator needs to create artificial, regularly spaced data — a process called gridding — from the field collected measurements. The resulting RFE approximates the field data collected and the real conditions of the site. This process can produce a misinterpretation of results.

LiDAR advantages

While LiDAR is subject to some of the same challenges as analog methods, it can address these challenges more successfully and reduce human bias in data collection and analysis. Examples:

As LiDAR collects information from all surfaces, the scan creates the site drawing, eliminating the dependence on existing site drawings and location inaccuracies associated with traditional data collection.

LiDAR further reduces human bias because all data points within the range of the device are collected – not just locations selected by a human operator – and incorporated into the cloud.

A laser conducts the measurement, so there is no need for the operator to physically reach the floor areas being scanned. This advantage allows for data collection in areas that otherwise might be difficult to access and reduces safety risks, since the operator does not need to go into a hazardous area to collect data.

LiDAR data does not require the gridding traditional methods do, reducing the overall post-data collection processing time. Data points from objects not associated with the investigated surface also can be filtered out easily.

The density of the LiDAR data point cloud allows for miniscule variations in elevation and gradient to be observed because spacing between measurement points is in the range of millimeters and results in a topographic map that more closely matches the true conditions of the site at the time of scanning.

The sheer volume and precision of LiDAR data allows for multiple calculations to be conducted, such as elevation gradient or surface roughness with statistical confidence and the mapping of joints, cracks and other variations. This data can be compared reliably, resulting in the ability to track the site's movement over time.

LiDAR captures information from its entire field of view – including walls, ceilings, roofs, stairs and risers – resulting in relative surface models of the site features that allow for a more comprehensive analysis of the building distress. While obtaining these measurements is not impossible with other methods, it would require a number of different devices and logistical efforts and would result in multiple discrete data sets. LiDAR collection allows for direct comparison of the multiple surfaces of a building in one data set.

Traditional RFE production is prone to data inaccuracy due to human bias and error, is limited by the small number of data points collected and yields results that do not represent the real conditions of the site. In contrast, LiDAR collection reduces human bias, increases operator safety and delivers high-density data that accurately represents real conditions all while providing a visual record of the site.

Robert Hendricks is senior staff geophysicist for the facilities group at the Dallas office of Terracon.

Related Topics: