Trained Immediate Responders Can Provide Swift In-House Action When Trouble Strikes

Whether they are police, firefighters or emergency medical service personnel, first responders are the ones who arrive at a crisis scene to provide emergency assistance and protection. But as important as they are, first responders are not the first on the scene. Someone has to call them, and it will be several minutes or longer before they can reach the site. What's more, there are the rare horror stories of 911 dispatchers sending rescue units to the wrong address or responders taking an inordinate amount of time to arrive.

The question that facility managers have to face is this: Is it acceptable to wait for first responders to arrive, or should there be a plan for immediate response to a wide variety of emergencies?

More and more, that question is being answered with the recognition that immediate response and action are crucial to save lives.

For facility managers, that means developing a plan that empowers in-house personnel to make a conscious decision to do something, rather than waiting for someone else to tell them what to do or corroborate the need for action.

Need For Action

The question of what sort of response is best came to prominence following the Columbine High School shooting incident on April 20, 1999, in which 12 students and one teacher were killed. At the time, the accepted response methodology was to respond with first line police officers, who would set up a perimeter and wait for the SWAT or hostage rescue teams to take over. Analysis of the incident showed that the initial responders might have been able to stop the shootings and prevent explosives from injuring the victims if they had pursued the shooters immediately and not waited for other support units.

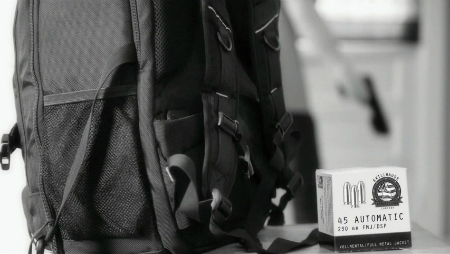

Since then, a new model has been adopted. This procedural change is important but there's a larger philosophical shift that is even more important. There's a growing recognition that, in the case of a so-called "active shooter" — someone intent on shooting people, with no interest in negotiating — individuals should always be prepared to take action to save their own lives, not simply wait for others to arrive and take charge of the situation. In other words, if there is an active shooter in the area, people need to decide quickly whether to run away from the shooter's proximity, barricade themselves in an office or work area, or do nothing and wait for help. The latter, if a person wants to survive, is not the choice to make.

Active shooter situations have become a grim part of reality, as incidents at Virginia Tech, Northern Illinois University, Louisiana Tech and other colleges attest. And behind the headlines about tragedies such as those are many other risks that facility managers should be prepared for. For example, during the period of April 2009 to April 2011, there were 113 bombs and bomb threats at U.S. schools and universities, according to NC4, a firm that provides incident information and analysis. The same firm reports that there were 72 shootings and six hostage situations.

Time Is Of The Essence

Statistics have shown that most active shooter scenarios are over within the first three minutes. That's roughly the amount of time, sometimes less but often more, it takes for the first responder to reach the crisis scene. What can be done in those first three minutes? Do your occupants and staff have the skills or experience (from drills and exercises) to be able to respond quickly? Prior to the Columbine High School shootings, most facility managers would probably have said that it was up to first responders to handle the situation. Since then, we have learned that the ability to assess the situation and take action is imperative to staying alive.

The question isn't limited to shootings. Facility managers should ask themselves: What other incidents occur that usually are over within the first three minutes before the first responders arrive? What they have in common is that a crisis occurs that has significant impact on the facility in a very quick timeframe with no build up or preparation. For example, in a bombing, police and firefighters would race to the scene and might soon arrive in overwhelming numbers. But the initial response would still depend on how close a roving patrol is to the site of the explosion. Until those first responders arrived, those on the scene would still be on their own for the first few minutes to assist victims.

Or consider the aftermath of severe weather such as a tornado. The harm and devastation are more widespread than with a shooting or a bomb. In fact, it might take in such a large area that first responders would be stretched too thin to be able to assist all who were injured. A hurricane might not be a surprise, given the weather tracking and communications technologies available, but the swath of destruction is on a larger scale than a tornado, with first responders potentially being victims themselves. Indeed, first responders might be concerned with ensuring the safety of their own families before being able to assist others. This happened during Hurricane Katrina; many police officers, fire fighters and emergency medical services personnel were involved themselves or were not able to respond due to blocked roads or flooding.

Related Topics: