New outlook on access control

Facility executives have taken a hard look at risks since the attacks of Sept. 11. Here’s what they’ve learned — and what steps are being taken — to reduce vulnerabilities

In the immediate aftermath of America’s worst terrorist attack, building owners and facility executives throughout the country huddled in emergency meetings to discuss what could be done to safeguard buildings. The primary focus was on immediate actions that could allay fears of a nervous public.

This call to action created two scenarios. The first scenario began with risk analyses as the basis for developing new or for changing existing strategic plans. From there, cost estimates were developed, primarily focusing on access control for lobbies and other entry points. Based on their needs, building owners and facility executives scheduled the orderly installation of the necessary systems, along with providing for the expansion and training of a security staff to implement these programs.

The second scenario saw building owners and facility executives ramping up the appearance of security at a frenetic pace, adding everything from concrete barriers and surveillance cameras to metal detectors and security officers. In many cases, the cost of the increased security measures proved prohibitive and the projects were curtailed or halted short of completion. Even worse, building owners and facility executives discovered their security staffs were incapable of operating and maintaining the sophisticated systems they had purchased.

Planning Pays Dividends

Now, two years after the devastating attack on the World Trade Center, a new outlook on access control has emerged. The starting point is planning. The purpose of an access control plan is to measure risk and provide appropriate responses. Risk analysis attempts to identify why, where and how a building may be penetrated. Is it a landmark building in a major city? Does the volume of people or the layout possibly lead to higher casualties or make it a prime target for terrorists? Do tenants include U.S. or foreign government agencies, abortion clinics, corporate data centers or other groups representing vital functions or controversial issues? A frank evaluation of these factors helps determine why someone would want to access a building illegally.

Determining where an intrusion could be made is a matter of examining all access points to the building, including doors, windows, HVAC ductwork, mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems, and other openings. The analysis of how the building could be breached hinges on considering all types of threats, ranging from a person with a weapon or a truck loaded with explosives to a tainted package arriving in the mail room.

The risk analysis provides the framework to develop appropriate responses to the various risks. Effective access control is based on integration of three design elements: architectural, technical and operational.

- Architectural elements include physical barriers to entry, such as walls, bollards, natural foliage (trees, berms), turnstiles (personnel barriers), force protection and hardened building construction.

- Technical elements range from video surveillance, metal detectors and card readers to biometric systems.

- Master plans, policies and procedures carried out by trained security officers make up the operational elements of the plan.

The final steps in planning include budgeting, implementing the program, training the security force and educating building users and tenants.

Today, facility executives place a high priority on access control. This emphasis can be seen in a number of emerging trends.

Fewer Entry Portals

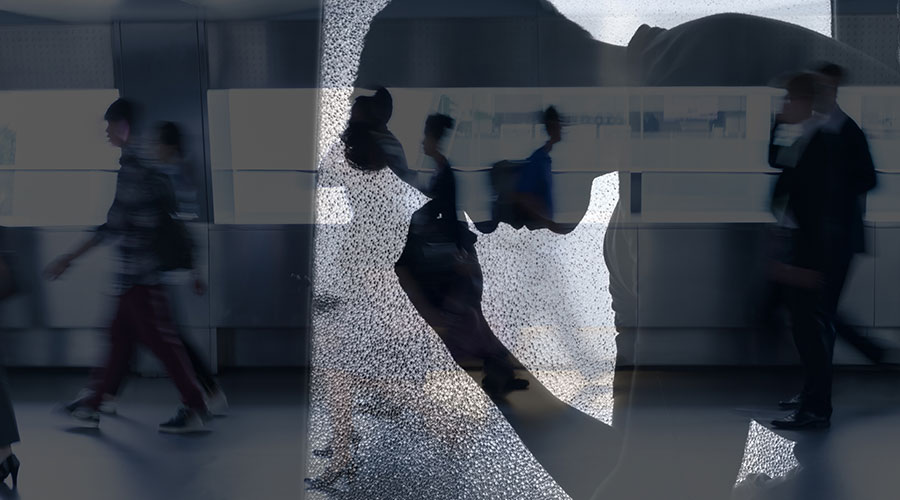

One key trend is a reduction in the number of entry portals. Starting with the tighter control of street traffic and pedestrian flow, facility executives are now providing fewer entry points to buildings. Channeling people through a limited number of entry portals slows the flow of people into the building, providing the time necessary for a security staff to detect illegal entry attempts and respond to emergency situations.

The number of entry portals also may vary by time of day. During hours of peak access — typically morning and noon hours in a high-rise office building — additional doors may be opened and staffed by security personnel and scanning equipment. These high-traffic hours are also times when a breach of the building is most likely to occur. When the building is closed, a single point of access can be staffed while other access portals are secured by video surveillance monitored from a building security center.

Facility executives also are focusing on closing off or restricting access to entry portals that weren’t considered in the past, such as loading docks, mail rooms and physical penetrations for HVAC and MEP systems.

This is arguably the most important access control measure a facility executive can take. Whether the facility is a public building, a corporate headquarters, a vital services site or a military installation, controlling who goes where and when is the foundation of a good building security program.

People are Key

As more surveillance and scanning systems are added to a building, there is a greater need for additional security personnel. The key point is, whatever security force is in place, facility executives must make sure personnel are qualified and trained to operate and maintain the access control systems. Security officers also must be keenly aware of how to respond to an illegal entry attempt. The key to staffing is quality, not quantity; the performance of a competent security officer must be enhanced by constant and thorough training.

Building users, including tenants, employees and visitors, are key to security, and the vast majority not only tolerate the minor inconvenience of additional security measures, but welcome the additional level of personal safety. This acceptance is increased by well-designed flow patterns and easy-to-follow signage that help get people quickly to and through access control points. Tolerance is also increased by professional, courteous security officers.

Today, the average citizen is alert to potential threats and willing to report suspicious circumstances to police and building authorities. The challenge for facility executives is to maintain this state of heightened awareness even in times of relative calm. This is done effectively through signage, the presence of security and regular security briefings and meetings with building tenants.

Communication and Flexibility

The lines of communication between building security and local, state and federal government agencies have been widened. Now, facility executives are involving police and fire officials in security planning processes. They are also calling upon specialists — particularly in the area of chemical, biological and radiological attack response expertise. Finally, with the Homeland Security Department in full operation, intelligence regarding potential security threats is being shared constantly and freely on a two-way communication channel.

Just as the Homeland Security Department adjusts the level of national security through its color alert system, facility executives also are adjusting their access control measures. Once a master plan has been developed for access control, it can specify which responses will be implemented in each of a full spectrum of security levels or prescribed circumstances.

For example, additional scanning of people and personal effects by security officers was implemented by many facility executives when the war in Iraq began. Airports began stopping and searching random vehicles before they reached the terminal buildings. The banking industry tightened security in response to intelligence from the Homeland Security Department.

Immediately after Sept. 11, many building lobbies were inundated with access control equipment, systems and staff. This produced a sense of chaos because normal building flow patterns were interrupted.

New Planning Priorities

Today, in both new construction and building retrofit projects, access control is being designed into the architecture rather than added on at a later date. Measures being employed include physical and optical barriers, card readers and metal scanning portals, individual search areas, biometric systems, and signage.

What’s more, attention is being paid to less obvious access points. As building security plans are being developed, attention is focused on all portals where any type of threat could enter the facility.

Planners are addressing access control issues on loading docks with responses that include formal security procedures and policies; video surveillance; training for security officers, loading dock supervisors and drivers on proactive steps to thwart attacks; and the hardening of the structure to withstand bomb blasts.

In the mail room, the emphasis is on awareness. Employees are being taught how to respond to a suspicious package. Policies and procedures are being implemented to contain and isolate potential chemical, biological or radiological incidents in the mailroom.

Tighter Control of Identity

A chilling fact is that the Sept. 11 hijackers all passed through airport security with valid identification. So the challenge for facility executives is to provide more accurate methods of identity verification, typically at the primary point of entrance to the building. Depending on the risk factor of a building, there are three tiers of identity verification:

Tier 1: “What do I have?”

At the lowest level of identity verification, a person must present an identification card — name, address, photo — to enter a building. Typically, a security officer checks the person against his or her identification card, which is issued by a government agency. If the card is issued by a tenant company or by the building itself, card readers are often used to validate the information.

Tier 2: “What do I know?”

At this level, people must possess identification cards and provide additional information to prove they are who they claim to be. This secondary validator could be a permanent personal identification number (PIN) or a code that can be changed on a periodic basis. To penetrate a building, the intruder must not only secure a valid ID card, but also provide the right PIN or code.

Tier 3: “Who am I?”

This represents the tightest access-control process possible. It uses biometric systems to read the physical characteristics of a person and match them to an approved database. These biometrics include fingerprints, iris and retinal scans, facial and voice recognition, and, in the future, DNA sampling. Even though these sophisticated methods significantly improve the odds of deterring illegal entry, they do not provide total security. A disgruntled employee, for example, could still be admitted and commit an act of violence.

Integration Is the Answer

Unfortunately, no compact, fast, easy-to-install or easy-to-use, affordable, 100 percent accurate access-control systems have been developed since Sept. 11. Nor is there a magic formula for access control or a shopping list from which facility executives can pick the perfect system.

True, technology has enabled more types of data to be encoded on “smart” cards, increasing the odds of defeating intruders. Biometric systems also have become less intrusive and more affordable for use in lobby-level access control. There also has been progress on developing systems to detect CBR agents.

But in essence, facility executives have had the majority of access control technology available to them prior to Sept. 11. There just wasn’t a mandate to employ the potential solutions. What has actually transpired since is that facility executives are using more of the available access control technology and security methodology. This focus on security with an emphasis on access control has provided system manufacturers with more feedback on current technology. The availability of practical information on real-world performance has enabled faster, more focused development of access control systems.

The best way to achieve the desired level of access control for a building is to develop an integrated solution to meet the specific needs of the facility. This is done by assessing risk exposure, analyzing the form and function of the building and then choosing technical systems and manpower levels that fit within the organization’s budgetary limitations and provide the results sought.

William Sako is the president of Sako & Associates Inc., a subsidiary of The RJA Group Inc., headquartered in Arlington Heights, Ill. A 30-year security veteran, he has consulted with corporations, institutions and governments throughout the world.

Related Topics: