Effective Immediate Responders Require Careful Planning, Training

How do facility managers address the need to respond before the first responders arrive?

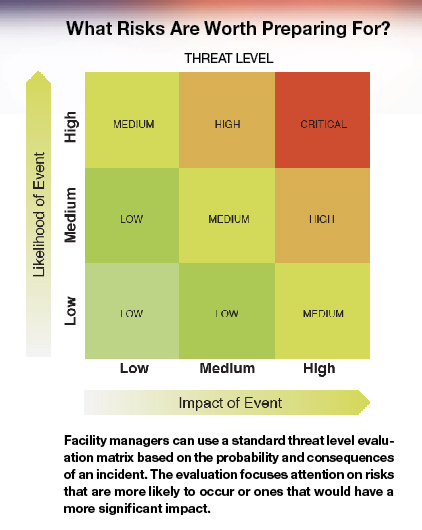

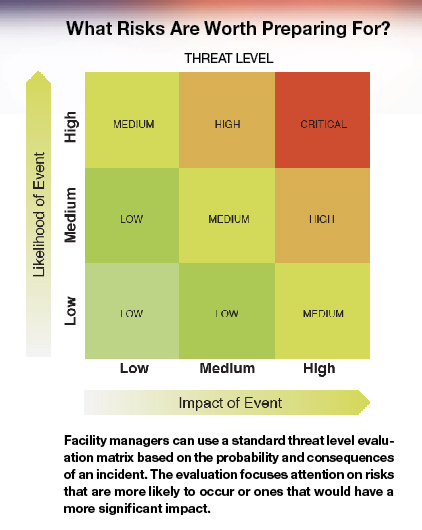

The first step is to determine risks and categorize them according to how significant they are and how often they occur. A threat level evaluation considers the likelihood and impact of each, then ranks them on a matrix to determine the risk level. (See "What Risks Are Worth Preparing For?" below.) The facility manager can then devote resources to threats that are most likely to damage the organization because of their strategic, financial or operational implications or because of issues of regulatory compliance or reputation.

Most of the risks or incidents that are normally over within the first two to three minutes are high impact but low probability, thus carrying a medium risk. But the specific level of risk must be evaluated for every facility. For example, the risk of a tornado may be rated medium in one part of the country, but high or even critical in areas where tornadoes are regular occurrences. Once risks have been evaluated, facility managers must decide what steps to take to mitigate the highest priority threats.

Immediate Responders

Included in these steps is assembling a team of immediate responders. Kennesaw State University has put in place a comprehensive program of immediate responders, known as crisis coordinators. The program began in early 2008, and has grown from 35 trained volunteers (initially one per building) to 165 immediate responders located throughout the campus.

The response varies depending on the type of incident. In the case of an active shooter scenario, immediate responders are trained in assisting with evacuation (moving away from the action) or sheltering-in (barricading themselves with others in a secure area) as part of "taking the lead." They are prepared to gather students, staff and visitors in storm shelters during a tornado warning.

The immediate responder program started with a focus on high-impact situations, but has expanded to address incidents that are low-impact but high probability. For example, immediate responders are ready to give CPR or use an AED in the event of sudden cardiac arrest. And they're prepared in the event of smaller events as well: slips or falls on stairs, fainting in class or sudden illnesses, to name a few.

Instead of asking "what should we do?" the immediate responders are trained to call for professional help — first responders — and to provide immediate assistance while awaiting the arrival of the first responders.

These immediate responders provide single points of contact during an emergency. These volunteers get significant training. They receive crisis management training that provides an overview of their responsibilities as crisis coordinators, the way they will interface with the police in emergency operations, terrorism awareness and indicators, and CPR/AED and first aid training. In addition, they are trained in the use of a fire extinguisher and learn to recognize and report hazardous materials and to understand a Material Safety Data Sheet. Once this training is completed, the next step is to pass four on-line National Incident Management System courses from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Once all of the training has been completed and documented, the crisis coordinator gets "coined." Instead of just getting a certificate to hang on the wall, the certified crisis coordinators receive a "challenge coin" from the department of strategic security and safety, which identifies them as immediate responders.

These immediate responders receive ongoing training as well, including drills that address all the scenarios identified in the risk assessment matrix, not just ones that are low probability but high or critical impact, but also many high-probability, low-impact situations.

The emergency response program also provides the equipment that may be needed in an incident:

- Orange, red or yellow crisis vests with pockets to hold equipment

- Flashlights and extra batteries

- First aid kits

- Mouthpieces for AED kits

- Walkie-talkie radios and extra batteries

- Red notebooks to hold floor plans, evacuation routes, fire exit locations, storm shelter locations, fire pull station identification and hazardous material lists.

In addition, buildings are supplied with equipment such as AEDs, and emergency evacuation chairs are being purchased.

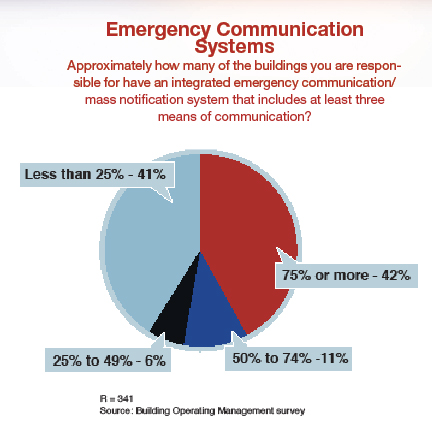

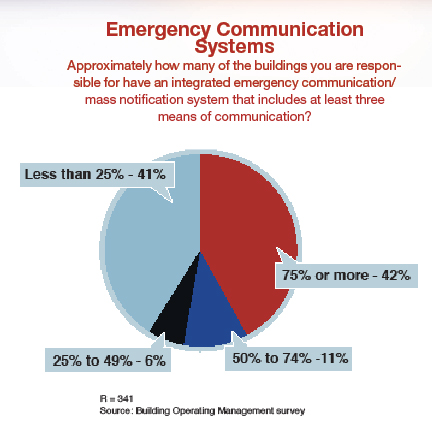

Kennesaw State also deploys a layered approach to emergency mass communications that is initiated while the immediate responders are performing their duties and that assists the campus public safety department in doing its job: responding to the incident. The first layer is a campus-wide siren and voice-over alert system used only for sheltering-in situations such as an active shooter, hazardous material spill or a tornado warning. The second layer is the emergency notification system that sends messages to the 30,000 subscribers via voice messages, text messages and emails. Because there are cell phone dead zones in buildings, Kennesaw State has also developed a network computer "popup override alert" in which any computer on the network, on both PC and Mac platforms, will receive a message of what to do in an emergency affecting the campus.

The future will undoubtedly see many improvements in emergency response programs and the technology that supports them. But one thing won't change: the need for immediate personal action from people who have been trained to take action.

Robert F. Lang is assistant vice president, strategic security and safety, and chief security officer, at Kennesaw State University. He was formerly the director of homeland security and director of research security at Georgia Tech University. During that time, he was the primary security planner for the 1996 Olympic Village. Lang has written frequently on security and safety issues.

Related Topics: