Remote Work Options: Who, Where, How, Why — and Why Not

Facility executives can solve some problems by offering employees a choice of different workplace locations. The trick is to avoid creating new problems

It’s Tuesday and the parking lot at headquarters is half-empty. That means:

A) The current recession has decimated the workforce.

B) Public transportation and ridesharing are finally catching on.

C) Professional staff is taking advantage of workplace options off campus.

If you answered “all of the above” you might be right, given current economic conditions. However, well before the recent downturn, smart businesses were exploring opportunities that allow staffers to be productive at work in a growing network of places. A confluence of forces — economic, demographic, geographic and environmental — has led to the unlikely embrace of a concept that is changing business culture across the country.

Even as corporate hierarchies lost their primacy to networked team environments in the 1990s, many managers still relied on the visual reassurance of seeing their people at work. Telecommuting seemed a sensible alternative for sales people or consultants whose performance was easily measured, but how would supervisors evaluate other staff when they could not check up on them throughout the day?

Where Are the People?

The reality is that, in studies of thousands of workers in leading companies, managers are hard pressed to find workers at their desks much of the time. Intensive on-site studies reveal that, on average, any individual workspace is occupied only 40 percent of the time. Where are the workers? Human resources departments report that roughly 10 percent of the work force is on vacation or sick on any given day. Then there are client meetings, conferences, lunch, travel time between buildings or other sites — the list goes on.

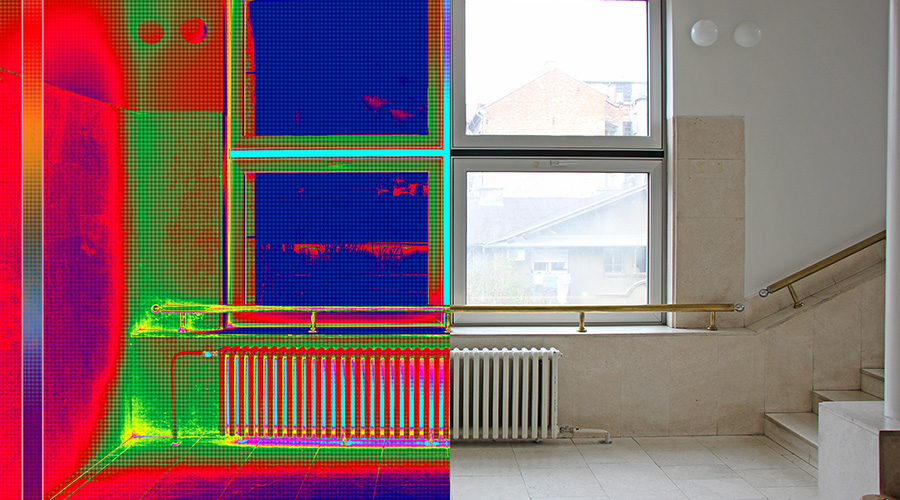

With workers at their desks less than half the time, there is a substantial opportunity for savings — in both occupancy and in energy costs — from increasing the ratio of worker-to-workplace even from 1:1 to 1:2 or five people instead of four in a work area. The larger the organization, the greater the opportunity, especially if the workers maintain or improve efficiency.

But savings, no matter how great, are not a substitute for strategy. Companies looking for real return on their facilities decisions are implementing programs that address not only occupancy cost but other critical issues, including quality of life concerns that affect recruiting and retention, environmental impacts and community perceptions.

Once senior management begins to analyze where work actually gets done, the workplace — in its broadest sense — can be reconfigured to maximize workers’ access to space and tools. At the same time, a move from a population-dense central campus to a dispersed network of spaces allows organizations to take advantage of regional geography to reduce commute times, often with the added benefit of lower real estate costs.

Whether it is the San Francisco Bay area, Boston and its suburbs, metropolitan Houston, or a dozen other locations, large numbers of employees live in neighborhoods or towns located miles from their offices. Workers around the country spend hours each day in traffic while they miss their kids’ soccer games and piano recitals and their own doctors’ appointments as well.

Options and Implications

Progressive companies are creating programs and places to offer employees a choice of several different workplace locations; these include work-at-home options and outer-ring drop-in workplace and meeting spaces, as well as offices and support at headquarters. The range of choices corresponds to the variety of requirements workers face as they juggle assignments from focused individual work to meetings with teams or clients to training sessions or major presentations.

Not every worker is a candidate for “away” options. It is critical for companies to develop a profile of characteristics for both the work and the workers best suited for off-campus success. Worker profiles coupled with an understanding of employee demographics (who lives where) and an analysis of commuter distances (how long does it take to drive over what roads) give shape to the program.

For example, a Silicon Valley technology company might find that it can provide accessible hubs for 75 to 80 percent of its workers who live more than 90 minutes away from the central campus by creating four or five work centers in various locations in the East Bay, downtown San Francisco and on the Peninsula.

Satellite centers with 10,000 to 25,000 square feet of workspace provide employees with access to technology, space for meetings with colleagues and clients, and a sense of being part of the company. While the workspaces at a typical remote location are unassigned and cannot be reserved for long periods, they are popular, busy places with utilization numbers running near 60 percent on average and close to 100 percent in the morning hours. The incentives of saved commute hours and just-in-time services far outweigh the complaints about lack of personalized space or privacy usually associated with unassigned space.

The acceptance of remote centers depends, in some measure, on the availability of a sophisticated work-at-home option. Companies need to face the liability and ownership issues associated with the furnishings and technology to provide workers with the tools and access they need to be successful. Advances in technology have already made the home office option an effective alternative for many; now, as “follow-me” phone numbers, broadband access and ergonomic furniture become more available and less expensive, the concept will become more appealing to workers and management alike.

These work options mean that an organization’s headquarters has fewer but more highly utilized workstations, meeting and training facilities, labs, and visitors centers. This is the essential infrastructure of company culture. Mobile workers return to the central campus regularly for a variety of reasons — group meetings, training sessions, the introduction of new products or processes, and client presentations. Being on campus gives workers an opportunity to reconnect with the larger organization, reinforcing the value-added aspects of corporate culture, such as knowledge sharing. Workers return to headquarters not to be evaluated but to contribute to and partake of the intellectual and cultural capital of the organization.

Issues and Bonuses

Although the pioneers of this approach to facilities report early successes, there are areas of serious concern. After years of creating highly specialized offices, companies are reconsidering space requirements — convertibility, not customization, is the watchword. Yet generic spaces raise the question of identity for individual workers. What is their territory? Where do they put their personal markers when they are constantly on the move? And what about storage?

A recent study indicates that paper consumption is on the rise. Homerooms at central offices can best accommodate artifact-quality documents, while remote hubs offer interim storage for project documents. Personal storage, that very human attachment to stuff, continues to be a sensitive topic.

Breakthroughs in technology have been the critical factor in facilitating the move away from centralization; however, many of those same advances have raised expectations about access and quality that are difficult to achieve in such diverse situations. Wireless communications have given individuals mobility, but at what cost to security? After years of counting on a T1 line or other high-speed solutions for Internet access, the dial-up 56k connection available in many suburban neighborhoods can frustrate productivity.

On the plus side, remote options get workers off the highways. Numerous studies by the U.S. Department of Transportation document the positive impact of decreased commuting; the potential in terms of energy savings, reduced pollution and associated transportation infrastructure costs is a powerful incentive for communities as well as corporations and individuals. Recouped commute hours give workers time to engage with their families, their communities and their work in new and meaningful ways. Workforce demographics indicate that, in spite of temporary economic setbacks, the search for talent will continue to be a key concern for corporations. For that reason, quality of life and quality of work issues — including time away from the office — will play a significant role in recruitment and retention programs.

Collaboration Springs from Culture

A lingering question for proponents of the expanded-options approach revolves around collaboration. There is a cherished notion of insights shared at the coffee bar or water cooler spawning new technologies, marketing campaigns or simply great ideas. In fact, serendipitous exchange is not critical to collaboration. Far more depends on a work culture that encourages interaction and sharing of information. Business cultures that reward teamwork and provide support — be it space, technology, training or encouragement — will benefit from collaboration.

The real question is not how to measure productivity but how to measure and reward success. Corporate cultures that leverage the independence of competent, committed individuals with work options that support effort will outpace competitors focused on control and cost savings.

John Duvivier is a partner in the Redwood City, California-based firm of Bottom Duvivier, which addresses workplace issues with solutions that range from software to interior design, from architecture to product design.

Related Topics: