5 Steps to Resilience Within Your Organization

Now is the time to apply the lessons learned during the pandemic about resilience and business continuity. Here's how.

The last few weeks have been exciting as we hear about COVID-19 transmission rates going down, mask mandates lifting, and limitations on social gatherings going away. It is a good time to reflect on what we have learned.

I have been thinking about the role maintenance and engineering managers have played throughout the pandemic and the roles they will play in their organizations going forward. The pandemic thrust managers to the forefront of their organizations to lead in emergency response and facility preparedness at a time when no one knew how the pandemic would play out and how long it would last.

Now that we see light at the end of the tunnel, it’s clear that managers have certainly learned something about business resilience and the importance of having more than an emergency response plan in place. To be resilient, the organization's business continuity needs and the facilities plan for responding to events must be connected. Whether an organization has a resilience strategy in place or it's a work in progress, managers can take several key actions to improve an organization's resilience.

1. Understand essential functions

Essential functions must happen for the organization to survive. The key for managers is to understand not just what these essential functions are. They also need to understand the facility management function's role in these functions. Managers are responsible for the organization’s assets, including such critical infrastructure as power and cooling. Here are some additional examples of essential functions:

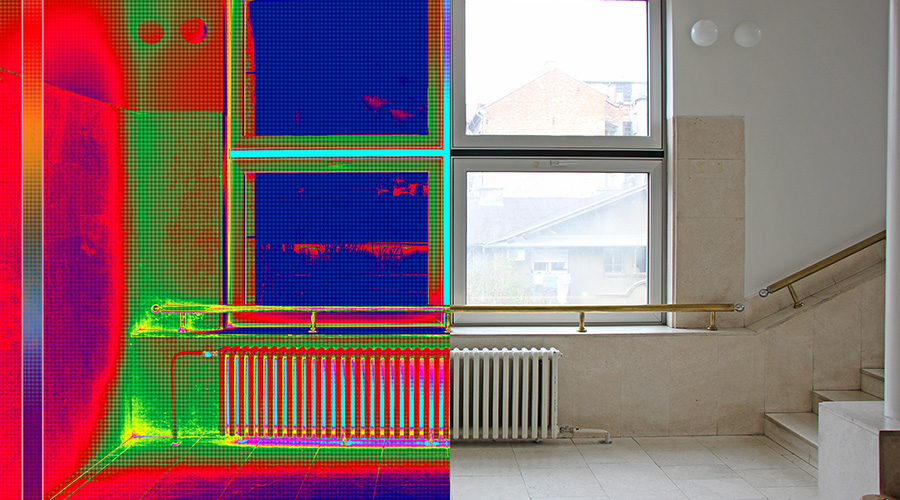

• Climate control for sensitive areas. These areas include data centers and laboratories. In one facility where a laboratory was an essential function, the manager understood that a loss of climate control could destroy crucial research. To protect it, the manager installed emergency generators as a primary backup for laboratory space conditioning systems and refrigeration equipment, as well as liquid nitrogen as an additional backup for critical freezers.

• Critical vendors. Managers need to identify key supplies and sources whose loss could interrupt the business, as well as vendors that might support the ability of the business to continue. In another example, a large manufacturing facility requires continuous power to operate. In addition to providing a generator system, the manager has an agreement with a vendor that will provide portable back-up power in an emergency. This arrangement gives the manager additional capability beyond the on-site infrastructure.

• Network connectivity. Managers must ensure staff can access needed files and records. While the IT infrastructure typically is not within a manager's purview, supporting those systems is within it, meaning managers need to provide alternate power and cooling sources.

2. Understand timing

Managers need to pay attention to the acceptable time frame for essential functions after which their loss begins to damage the business. In a critical laboratory or a data center, for example, that time might be as little as a few minutes.

For other functions, managers might have up to a few days. For example, if processes or products can be shifted to another location, managers might be able to buy margin on system repair time. This situation is important for managers to understand so they can scale back-up options to fit the need.

3. Understand teams and roles

An effective resilience strategy lays out roles and responsibilities. One thing organizations learned during the pandemic was the importance of acting as a team, which includes facility management, organizational leadership, legal, IT, and human resources. In an emergency, a maintenance and engineering manager's role is often to advise and execute. That is typical in fast-acting emergencies such as a loss of power, system failures, fires, floods and earthquakes.

But during events that unfold slowly, such as the pandemic, managers can find themselves in a leading role in making sure essential facility functions have been maintained, sustained, and in the case of HVAC systems, bolstered to provide enhanced performance and safety. Over the last two years, managers have worked more prominently and regularly with other departments, sorting out critical decisions, the responsible party, how they would be executed, and how they would be communicated so the general population could understand the way the organization was continuing to respond and the outcomes they should expect.

4. Practice, practice, practice

Sometimes in discussing training events, we talk about building muscle memory. In a facilities context, this phrase refers to regular training so when an actual emergency occurs, the organization and the individuals in it know instinctively what to do. Their training essentially kicks into gear, and responses become automatic.

If you are like me, your thoughts went to fire evacuation drills and earthquake drills, and you might believe you have these situations covered. But think bigger. In prepared, resilient organizations, success takes much more than conducting emergency drills. It takes thinking on the enterprise level.

Resilient organizations educate their teams on procedures, plans and policies. They practice their procedures, and through that practice they build a prepared workforce that knows how to respond. What does practice look like?

• Drills. We grew up with drills. Typically, event-specific drills test a particular procedure, such as lock down, lock out, fire, tornado, or earthquake. Drills help us practice quick responses.

• Tabletop exercises. Key personnel verbally walk through a simulated scenario, playing their roles in an informal setting. Tabletop exercises are effective in testing policies, plans and procedures. They also test individual responses and team readiness. In one vivid emergency response tabletop I attended, one of the participants figured out the role they were supposed to play was a bad fit for them. Fortunately, we figured this out in an exercise where adjustments still could be made with little impact on the team. In other tabletop exercises, we have reinforced expected roles, such as essential functions that need to be addressed and how, who makes certain decisions, who communicates decisions, and how communication should be handled. In some organizations, first responders are invited to attend so they can understand the plan and offer insights.

• Functional exercises. Where a tabletop exercise is like a Hollywood table read, a functional exercise is a “cameras rolling" event. People act out their roles. A functional exercise simulates a scenario in real time, creating pressures that can help team members understand areas of strength and weakness.

5. Understanding what you learned

One important benefit of developing and implementing a resilience plan, training to it, and practicing against it is that you can see the holes in the plan. The same is true for real events. While my own team practices through drills and tabletop exercises, we also have had the benefit of real-life events in the last five years that have tested our resilience: fire evacuations, significant snow events, and of course, a pandemic. We have regrouped to see where things went well, where they didn't, and where we need to improve.

The pandemic has been particularly helpful in providing opportunities for continuous improvement. A two-year event will do that. With each exercise or real event, we become more practiced at the roles we play within the team, we understand what to do, and our confidence in our ability to respond has improved. We have increased our resilience.

Managers are critical to organization resilience. More than just keeping facilities operational, managers have a responsibility to help the organization focus on what is most important, connecting the dots between essential functions and preparedness so when a crisis strikes, little is lost, business impacts are few, and people are kept safe.

If you think these are big shoes to fill, you're right. But also remember this: as the manager, you know your organization and the way the people in it think. You are uniquely positioned to help your organization prepare and succeed through preparing and practicing resilience.

Laurie Gilmer is vice president and chief operating officer of Facility Engineering Associates. Gilmer is a published author and instructor and is the first vice chair of IFMA’s board of directors. She also serves as IFMA's liaison to ASHRAE's Epidemic Task Force and serves on the National Visiting Committee of Building Efficiency for a Sustainable Tomorrow (BEST) Center.

Related Topics: