Selling the CEO on HVAC Upgrades

OTHER PARTS OF THIS ARTICLEPt. 1: This Page

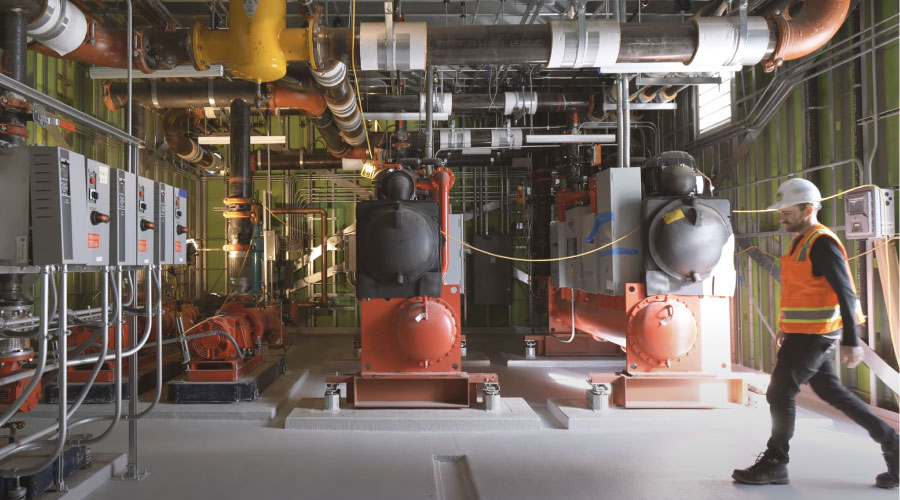

Your building is cool in the summer and toasty in the winter, but the HVAC systems are ancient. Should you wait for them to break down, or try to convince top management that it’s time to start replacing them — before something bad happens?

Facility executives are often confronted by that question, but are not always confident that they will always hear a “yes” if they ask senior executives. Merely pointing out that a piece of equipment is beyond its useful life may not be enough to overcome competition with other pressing capital projects. But with a bit of preparation, a good case may be made without needing a calamity to prove the point.

Many building systems are critical to keeping a business running. A failure of HVAC systems will very quickly be perceived by occupants if they become uncomfortable, or their work is disrupted as a result. A 1999 study by the Disaster Recovery Journal found that, among other reasons companies have declared a disaster, potentially requiring evacuation or business shutdown, 11 percent of respondents cited HVAC failures.

When unseen HVAC equipment is running properly, however, many forget that it is the main bulwark against being too hot, cold, stuffy or smelly. But when a valve leaks, a radiator fails, a fan becomes noisy, or a chiller is sluggish, productivity may be quickly affected as occupants are distracted or start to complain. The horror stories of HVAC failures that follow come from HVAC professionals who preferred to remain anonymous.

The Overheated OR. Surgery may involve life-saving or life-enhancing activity that cannot be easily postponed or moved. During the spring, one operating room (OR) was occasionally a bit warm; keeping it at the required 65 F was often a struggle. To address the issue, chilled water temperatures were reduced and fan speeds raised, costing extra energy, but still failing to deal with the real source of the problem. Many of the building’s three-way mixing valves, which control chilled water flow to cooling coils in air ducts, leaked chilled water into return water lines, causing chilled water to bypass coils — including those in the OR’s cooling system.

As the first hot days of summer arrived, temperatures in the OR approached 78 F, much too warm for medical personnel wearing layers of sterile gowns. Because sweating on patients is a no-no and groggy surgeons could make serious mistakes, the OR had to be shut down until the valves were replaced, causing expensive — and potentially life-threatening — delays. The valves should have been replaced when it became obvious that cooling was being lost due to their failure.

The Disabled Damper. During a chilly winter, some outside air dampers sometimes got stuck in the open position. While this caused heating coils in air ducts to work harder to warm up the extra air entering the system, comfort was still maintained (at a higher energy cost), so no action was triggered. On one very cold night, however, the unnecessarily high cold air flow froze the water moving through a heating coil, causing the coil to split. When it thawed out the next morning, hot water poured out of the coil, down through the hung ceiling, and onto the tenants. The fresh air system had to be shut down (technically a code violation), spaces evacuated, furnishings replaced, and tenant feathers unruffled.

The Foiled Field Trips. A popular museum was looking forward to the spring field trips from the local schools: Admission and gift shop revenues always jumped when the kids arrived. But this was a warm and muggy spring, and the building’s chiller was feeling its age. Like many of the museum’s artifacts, it too was an antique.

When the museum’s doors flew open, and scores of children entered, cooling loads quickly rose. Shortly thereafter, temperature and humidity alarms — which warn when conditions harmful to artifacts exist — went off. To protect the irreplaceable items, it was necessary to evacuate the building, close the facility to all but employees, and move many of them to a single wing. Why? All outside air flow had to be stopped to maintain proper art storage conditions, but working without fresh air was both unhealthy and a code violation. Until the old chiller (now so obsolete that new parts were unavailable) could be replaced, all field trips had to be cancelled, costing the museum an entire season of revenue.

The Raging Rooftop Unit. Due to years of neglect, a rooftop A/C unit’s air filter and cooling coil were caked with dirt and debris. Air flow across the cooling coil was limited to the point that refrigerant passing through it remained liquid instead of vaporizing. The unit’s compressor then received that liquid as large droplets that caused “slugging,” producing a sound like someone hammering the machine from the inside. Eventually, the compressor self-destructed, causing complete loss of cooling and shutdown of part of the building until a new unit was installed.

The Case Of The Poisoned Drain Pan. Moisture condensing on cooling coils dries humid air, making a space more comfortable. The condensate drips into a drain pan and runs down drain lines so it does not build up in the unit, which could be a single room’s fan coil or an air handler serving many rooms. Failing to keep those drain lines clear resulted in stagnant water building up in drain pans that, when continuously wet, also captured dust and dirt from the moving air. Such contamination is a breeding ground for Legionella bacteria, which cause Legionnaire’s Disease (a form of pneumonia).

A consultant examining the system reported it to the building owner. Out of concern for their own safety, however, the building’s cleaning personnel refused to clean the moldy pans. The owner was then faced with shutting down rooms served by the contaminated systems. To ensure the job was done to the tenants’ satisfaction, a specialized and expensive cleaning service had to be engaged.

Persuasion 101

Such horror stories underline the importance of staying on top of the HVAC system, but trying to scare management into action by citing them may not be effective. When asked how they have successfully made their cases, three basic themes emerged from interviews with facility executives, operating staff and consultants.

- You won’t get to first base without hard information on the condition of a piece of equipment.

- Never go into a boardroom with only one reason to replace; two is a minimum.

- Every supporting argument should relate back to revenue, cost, value or a combination of those factors.

Here are the most often-used criteria in such discussions:

- Energy efficiency: How much could be saved with a new unit?

- Code compliance: Is the unit causing a code violation (e.g., health, fire, building)?

- Reliability: Does it conk out often enough to irritate occupants?

- Capacity: Have loads or its output changed to a point where it’s not doing the job?

- Liability: Could a failure cause a lawsuit, insurance claim, or damage products or furnishings?

- Tenant satisfaction: Could replacing it improve service quality?

- Facility positioning: Could replacement offer a basis for higher rent or better tenants?

- Appearance: If the system is visible and ugly, would a new unit look better?

At least two of these points, each with supporting documentation, should be used when presenting a case.

Information Is The Foundation

All these issues have one thing in common: they demand information. “The chiller is acting funny,” for example, is not hard data and is unlikely to elicit a financial commitment for a new unit. Instead, the key to making a successful business case hinges on collecting objective facts and providing a professional perspective.

Such data may already exist in the form of chiller logs, work orders, inventory records, customer complaints, and other facets of good facility management. In other cases, it may be necessary to bring in an independent consultant to characterize a situation or add new methods of data collection (e.g., submeters, measurement points in the building automation system).

The most important thing is to keep good maintenance records that track the frequency and cost of service calls for major and critical systems. Without a track record of breakdowns, repairs, etc., it may be difficult to support a claim of impending failure. Merely carrying a notepad and a digital camera, such as in a cell phone, may also help document problems like spots on ceiling tiles that indicate future problems. Such pictures (or video) may be worth more than a thousand unsupported pleas.

A variety of processes and systems exists to collect and digest such information. Nearly all may be purchased as PC-based software. Most facilities, for example, have some form of work order tracking system to track the labor hours and responses to complaints involved in HVAC repairs. Such data may be combined with related information (e.g., warranty, inventory, checklists, schedules for preventive maintenance) in a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS).

A CMMS may automatically generate work orders for such things as routine lubrication, inspections, testing and meter readings — all of which serve to monitor equipment and keep it running properly. Keeping such records may also provide the information needed to make a case that a given piece of equipment is not responding to such “life support” and needs to have its plug pulled.

Instrumentation may also provide useful information. Think about your car’s dashboard: When the temperature gauge shows the needle in the red zone, it’s time to pull over and check your coolant level (or maybe call AAA). Likewise, the oil light, check-engine light, and air bag indicator each tell us something important. The same is true for measurement points reporting motor temperature, speed, vibration, power draw, etc. Each may provide a warning of trouble or need for maintenance when they pass pre-defined limits. Such “conditional monitoring” may be part of a preventive or predictive maintenance program. Having such programs over the lifetime of major equipment may show trends that, if not addressed, could lead to catastrophic failure — and economic damage.

In the end, seeking financial support for better maintenance and related data-gathering and -management systems may be as worthy a struggle as getting money for a new chiller. The techniques for securing funding are the same for either goal.

When you don’t have such data, calling in an independent engineering consultant may be the best way to generate it. Doing so also provides a credible outside source with no ax to grind. Rather than initially arguing for replacing an old chiller, for example, it may make more sense to first secure funding for a needs assessment from an experienced consultant. If the professional analysis concludes that the chiller must go, the report can make the case through a cost-benefit study that addresses paybacks and the risks of inaction.

Translate Operations Into Value

Asking for a large capital allocation is not a subject for a short in-the-hall discussion. It should instead be approached as a business case: Briefly describe the opportunity, quantify the benefits and risks and recommend how gains will be achieved. Avoid technical jargon and use the organization’s preferred economic criteria (e.g., total cost of ownership) for making financial decisions. Ask the CFO’s office for guidance on how others seeking funding have made their case and use a past successful proposal as a template. Whenever possible, emphasize positive benefits rather than just negative consequences. While it’s true that a chiller failing in the summer could force a shutdown until it’s fixed or replaced, it may be better to initially communicate that issue through the value the company produces when building temperature is properly maintained in dollars per day, for example.

Look for several ways to express economic value, such as cutting energy costs with a more efficient unit, reducing maintenance overtime and avoiding possible fines from code violations. Be sure to ask the manufacturer of the new unit for additional ways to pitch your proposal. And don’t forget to include any direct financial incentives (e.g., utility rebates, tax credits, accelerated depreciation) that may be available. Always make the case using at least two major arguments that are not directly linked to each other. For example, efficiency and code compliance. Doing so will increase the likelihood of approval.

If pictures and data are not sufficient, invite the decision-makers to view the situation firsthand via a tour of the equipment. But don’t expect non-technical people to immediately grasp that a problem exists. Prepare them in advance by describing how the machine works and what symptoms indicate it’s not doing so properly.

Back in the boardroom, describe the consequences of a failure in non-emotional terms: for example, the possible need to relocate tenants for X number of days or potential damage to furnishings from flooding. Using the facility’s disaster response plan, describe the actions that would need to be taken under that plan. If no such plan exists, and the proposed replacement is not supported, ask for resources to develop an emergency contingency plan to handle a possible equipment failure. Framing the situation in that manner may make it more real.

Be sure to ask that meeting minutes be generated for future reference. Request that the minutes reflect that you provided information on the possible ramifications on that date so it is clear that senior management were fully informed. Doing so may help protect your position should a serious problem later result. Sometimes merely establishing in writing senior management’s responsibility for a possible future disaster may result in closer consideration of your proposal.

CLICK & VIEW

Rules of Thumb: Investing in HVAC System Maintenance

|

Lindsay Audin is president of EnergyWiz, an energy consulting firm based in Croton, N.Y. He is a contributing editor for Building Operating Management.

Related Topics: