Managers who adapt their current practices on sustainability can help their department achieve the ultimate goal of sustainable, strategic management.

Managers who adapt their current practices on sustainability can help their department achieve the ultimate goal of sustainable, strategic management.PGMS: 3 Key Principles on Sustainability

Understanding the three key principles of sustainability can help managers produce high-caliber results. Prepared in conjunction with the Professional Grounds Management Society.

Principles into action

The three key principles of sustainability help guide the best grounds management practices, which are the actions institutions take to produce high-caliber results. It is important to note that while it is one thing to have best practices, it is another to monitor and review those practices to ensure correct implementation and effectiveness. Managers should examine and adapt these practices frequently to ensure a successful program.

Within the social responsibility category, one key factor is that natural processes and human activities coexist. A best practice is incorporating an event management plan with grounds maintenance strategies that would allow for collaboration between stakeholders and grounds personnel. The plan should find a time and location that “offers the least negative impact on the maintenance of green and open spaces, which ultimately contributes to the sustainability of the landscape,” according to PGMS: A Guide to Grounds Management Best Practices.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of effective communication regarding the implementation of maintenance activities and their effect on sustainability goals. The rationale behind one of the key principles of environmental stewardship — providing leadership and effective communication — is to educate the organization’s customers on the environmental correctness of maintenance activities to eliminate misconceptions and conflicts. Managers can use internal and external media outlets to publish and disseminate information, specifically on grounds maintenance activities.

For example, the University of California, Davis (UC Davis), a four-star PGMS accredited campus, reduced its landscape irrigation by more than 67 percent from 2011-2013 following a state-mandated water reduction of at least 20 percent. The university’s arboretum and public gardens teams attributed their success to integrating water conservation, native grasses and high-efficiency irrigation systems, with the latter practice emphasizing an important element of grounds management — staying on top of the latest technologies available.

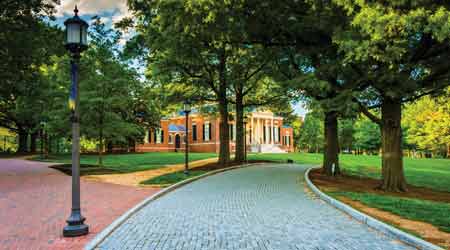

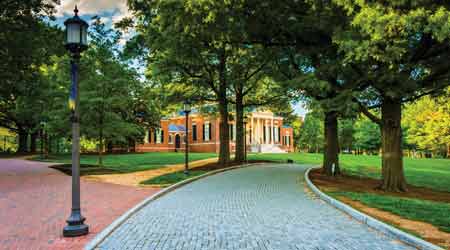

Looks matter

The increasing desire to reduce the use of resources has led to managers with many organizations converting high-maintenance areas to minimal-maintenance landscapes using regional, drought-tolerant plants. In many cases, this practice reduces the need to mow, trim, prune and edge.

But it also can create a wild appearance in the eyes of students, staff, visitors and faculty in the case of a university. Invariably, these types of landscapes require maintenance to prevent hazards, weeds and silting, and they can attract wildlife, such as snakes, insects, birds, and rabbits, some of which might not be desirable.

Institutions shifting toward more natural landscapes are showing increased interest in creating, implementing and managing an integrated pest management (IPM) program. For example, Western Michigan University, a four-star accredited campus, highlighted its comprehensive IPM program during its accreditation process.

The campus’s written objectives included: eliminating significant threats from pests to the health and safety of students, staff, and the public; controlling erosion and sedimentation for landscape operations and future construction activity; and diverting landscape cuttings and clippings from the waste stream via mulching, composting, and other low-impact practices. Such clearly stated objectives and plan coordination ensure effective expectations and implementation.

Managing campus aesthetic expectations also requires creativity. Cary Avery, certified grounds manager at UC Davis, replaced synthetic fertilizers with organic fertilizers and focused on the use of compost and compost teas to improve soil conditions and plant health. The result was improved root growth, which saved water. The campus also began mulching with recycled green waste from tree trimming operations, which improved soil conditions and conserved water in plant beds.

Related Topics: