The Teck Acute Care Centre at BC Children’s Hospital, which opened in 2017 in British Columbia, maintains a three-day supply of potable water for all hospital functions in the event an emergency cuts off municipal water.Ed White Photography, courtesy ZGF Architects

The Teck Acute Care Centre at BC Children’s Hospital, which opened in 2017 in British Columbia, maintains a three-day supply of potable water for all hospital functions in the event an emergency cuts off municipal water.Ed White Photography, courtesy ZGF ArchitectsReal-World Water Resilience: A Case Study in Water Efficiency

A large hospital facility in British Columbia shows how water efficiency strategies create water resilience.

While facility managers are getting a handle on water use in their facilities, it makes sense to deploy all the easy water-efficiency strategies that are readily available on the market today. This includes putting aerators on faucets and using low-flow showerheads and low gallons-per-flush toilets and urinals. Sensors on toilets and faucets should be properly calibrated to rein in serial flushes or unnecessarily long-flow times. Landscape irrigation should be recalibrated so grass isn’t being watered while it’s raining, for example. Better yet, replace water-intensive non-native crops with native landscaping that can survive on less water. Consulting the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s WaterSense program to find equipment that uses water efficiently is a good idea.

Education is an important first line of defense as well. Having aerators in place will not achieve full benefit if facility occupants let the faucet run or don’t report malfunctions in a timely fashion. “People tend to think that technology will solve a lot of problems, but you have to marry that technology with changes to human behavior and practice,” Howard says.

Almost all new buildings, and many existing buildings, have deployed these front-line water efficiency strategies. These are important to being good stewards of water, and will help keep utility bills in check, but they don’t go all the way to making a facility water-resilient. This requires more involved strategies. Among these are the usual suspects of grey water reuse and rainwater capture for irrigation.

Another next-level step is minimizing the water consumption of large process loads, like chillers and sterilization equipment. At the pinnacle of water resilience: advanced measures like onsite long-term water storage, onsite waste water treatment, and becoming net-water-positive by recharging the water table. In the wine industry, stormwater is sometimes diverted to the dormant fields to percolate back into the water table, says Prigge. Another net-positive option is feeding treated water into wells to send it back into the aquifer.

Real-life readiness

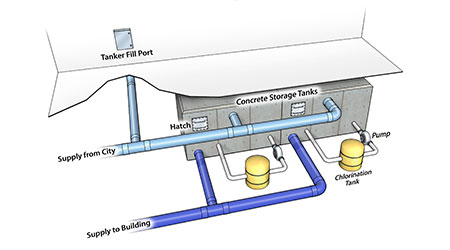

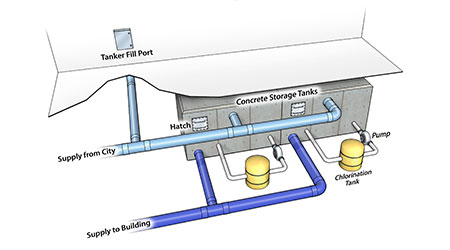

An example of water resilience can be seen at the Teck Acute Care Centre at BC Children’s Hospital, a 640,000-square-foot facility in British Columbia, which serves the region’s most critical pediatric and obstetric cases. British Columbia’s Provincial Health Service Authority mandated that the facility, which opened in October 2017, maintain a three-day potable water supply. This was calculated using the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) guidelines for acute care facilities of 50 gallons per patient bed per day. It is met by two concrete storage tanks, which are fed by municipal water that continuously flows through the tanks under normal operation to keep the water fresh. The tanks can be refilled by tanker truck in the event of a prolonged utility outage. The site also has a sewage tank designed to hold 24-hour’s worth of waste.

The hospital took steps to minimize its water demand, most notably by installing water-to-water heat recovery chillers, air-cooled heat recovery chillers, and air-source heat pumps mounted within the warm exhaust air to boost efficiency, says Sean Lawler, project manager and mechanical engineer at Affiliated Engineers Inc. He was the lead mechanical engineer for this project. The HVAC system is sized to allow for a 15 percent increase in demand over time due to warmer temperatures, or clinical demand. “There’s no cooling tower, so there’s no makeup water,” says Lawler. “If there was a disaster, there would be no additional demand to keep the HVAC system operational. The only water demand would be for the fixtures and process sterilization.”

The plumbing fixtures were designed to meet a 34 percent reduction over LEED baseline. In addition, sterilization equipment helps save water by using chilled water effluent cooling. Instead of mixing in additional cold potable water to bring the sterilized waste condensate back down to below 140 F, the facility uses a heat exchanger to avoid using potable water and allow the heat to be recaptured and put back into the building’s heating and domestic hot water system, says Lawler.

The northerly climate of British Columbia did help facilitate the water reduction strategies in the HVAC system, says Lawler, but even facilities in much warmer and humid environments could benefit from air-cooled or water-to-water heat recovery chillers, especially in lab and healthcare facility types where there is a high year-round demand for heat. The challenge in a warmer or more humid area would either be cost or finding enough space for the equipment. The standard 25-year lifespan of major HVAC equipment creates a natural reason to evaluate whether these HVAC-related water-reduction options make sense for a facility.

Taking access to water for granted is a risky proposition. “It’s been a miracle of modern engineering and design that for the past 100 years we’ve been able to treat and distribute drinking water fairly efficiently, in a secure and reliable manner,” says Howard. “We’ve taken that for granted.” But facility managers don’t have to wait until their own municipality’s Day Zero is looming to take make sure their taps don’t run dry.

Related Topics: