Buildings Go Net-Zero Energy, Tackle Climate Change

No longer just for boutique buildings, net-zero energy is a goal increasingly within reach. Even existing buildings that plan for "zero over time" can get to net-zero energy.

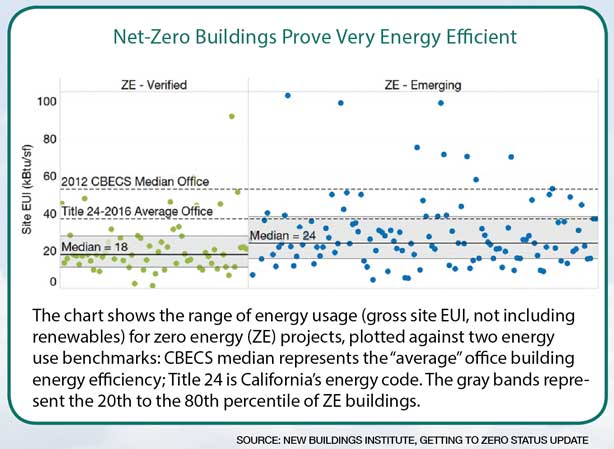

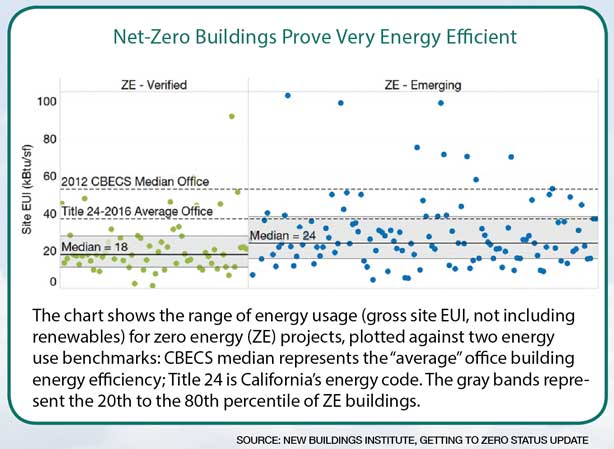

According to New Buildings Institute’s annual Getting To Zero Status Update report, the median energy use intensity (EUI) of the dozens of verified net-zero energy buildings included in the report is 18 kBtu/sq. ft./yr. By way of comparison, per Energy Star Portfolio Manager data, the national average EUI for a K12 school is 48 kBtu/sq. ft./yr., and for most building types the EUI is higher.

Simply put, the less energy a building uses, the fewer solar panels are required to make up the difference in a building’s annual energy use to be net-zero energy. “I think investing in energy efficiency is key,” says Jungclaus, “You have to think beyond the quick payback, no-brainer measures.”

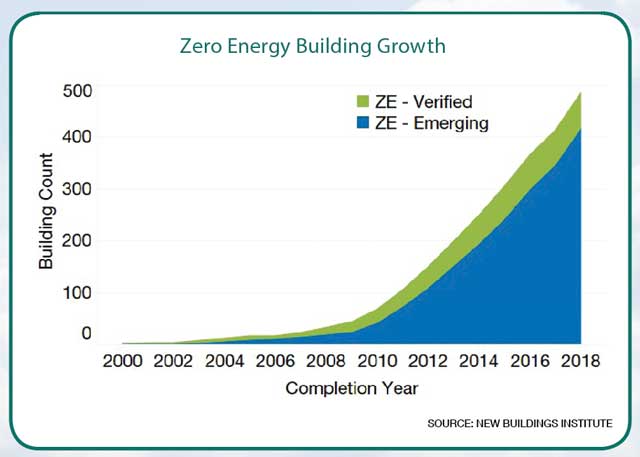

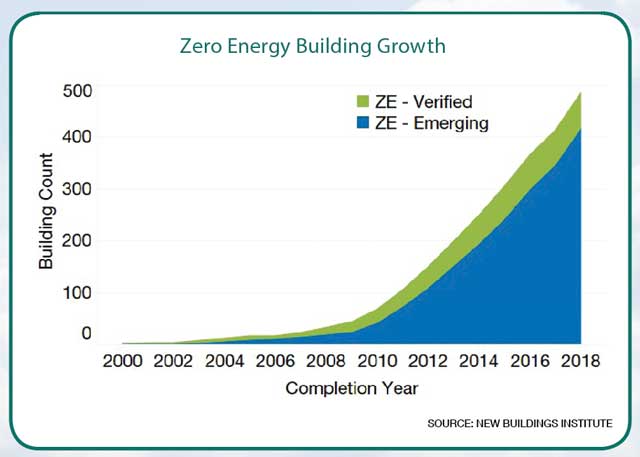

In most cases, net-zero energy is still a new buildings strategy, albeit one that is growing rapidly. The Getting To Zero Status Update study reports that the number of verified net-zero energy buildings has increased 700 percent in the last six years. Fifty-six percent of these net-zero energy buildings are either schools or office buildings, illustrating it’s no longer the tiny boutique buildings that are getting to net zero energy.

“Net zero energy performance is certainly possible for organizations that own their buildings,” says Miller. “New construction, of course, is most achievable since the project is starting with a blank slate and the design team can make important choices in terms of daylighting, natural ventilation, and advanced technologies that will optimize efficiency.”

Those strategies must be incorporated into the earliest stages of planning for a new building, says Jungclaus. “Frankly, in many cases, net-zero energy is a no-brainer for new buildings,” he says. But existing buildings are a bit more challenging. Indeed, is it even possible for the average organization with an average stock of buildings to get them to net-zero energy?

Difficult, but not impossible, say experts. “Net zero energy is also feasible in existing buildings through efficiency upgrades and operations monitoring to ensure that energy demand is minimized,” says Miller. As is the case with new buildings, the most important thing is the right kind of upfront, long-term planning. Large-scale adoption of this goal for existing buildings would put a huge dent in greenhouse gas emissions. “Existing buildings are a much harder nut to crack,” says Hughes. “But the more concentration on getting existing space to low carbon, the better.”

Zero over time

One strategy Rocky Mountain Institute has pioneered is what’s known as “zero over time.” The idea is getting existing buildings to net zero energy over the course of 20 years or so by investing heavily in deep energy retrofits and smart efficiency at major points in the life-cycle of a building, when the HVAC or major exterior elements need to be replaced, for instance.

“This approach relies on investing at the right times,” says Jungclaus. “You have to put together an upfront plan and align it with a capital plan.” Even if the organization doesn’t plan to hold the building long-term, investment in efficiency on an ongoing basis “positively affects the net operating income of a building, and that increases the resale value,” says Jungclaus.

These results must be measured and verified, proving the value of energy efficiency, as well. “For too long, building energy performance relied on modeled predictions about how much energy the building would use,” says Miller. “Often those models would fall short. With the pressure of climate change increasing, it has become critical that we confirm that actual energy use and carbon reductions are being achieved.”

Verification of performance is the way the industry is moving on a number of fronts, says Miller. The value of green building certifications like LEED and the Living Buildings Challenge is not only do they verify performance, but also they constantly raise the bar on sustainability performance for all buildings. One example of this, Miller says, is the growing efficiency of LEED buildings. “Our research has shown that most U.S. Green Building Council LEED Platinum buildings and many LEED Gold buildings are achieving efficiencies on par with net zero energy performance whether or not they have installed the requisite renewable generation,” she says.

Even a decade ago, today’s LEED Platinum performance, net-zero energy, or carbon neutrality would’ve seemed like moonshots. Today, not only are these strategies becoming increasingly possible, they also make financial sense. And that’s where the rubber must meet the road on climate change mitigation. Greenhouse gas reduction and climate-change-focused strategies must make business sense. “It’s unfair to expect the business community to take action at the level necessary to mitigate climate change if it doesn’t make business sense,” says Hughes. But due to the heightened awareness and acceptance of climate change, as well as the straight dollars and cents justification of efficiency, it’s increasingly clear climate change mitigation strategies really are more than just high-minded environmentalism. They’re the new standard operating procedure for business. “The real risk is not doing this now,” says Jungclaus.

Email comments and questions to greg.zimmerman@tradepress.com.

Related Topics: