The Human Factor

To minimize fire risks, look to the role of occupants both before and after a blaze breaks out

The numbers are sobering. More than 3,000 people die and more than 18,000 people are injured in the U.S. every year because of fires, according to the Society of Fire Protection Engineers. Beyond the human toll, fires cause roughly $10 billion in property damage annually.

Those grim statistics explain why commercial and institutional buildings are governed by strict codes and equipped with sophisticated fire and life safety systems. But clearly significant fire risks remain. Understanding the nature and scope of those risks is key to managing them.

The most obvious way to address fire-related risks is to prevent fires. Facility executives are well aware that offices, schools, hospitals, hotels, malls and other large buildings are packed with fire risks. Facility executives typically think of portable heaters, small cooking appliances and smoking materials such as cigarettes as fire risks. And they are. But the real source of risk may come as a surprise to facility executives. It’s human beings, say experts. People are the ones whose carelessness, like leaving a portable heater on after they’ve left the office for the weekend, leads to fires.

“You hear a lot about electrical fires and while wires do short on occasion, most of the time people at the end of a work day or week forget to shut off a microwave, a coffee pot or a computer,” says George Capko, vice president and engineering hazards manager with FM Global. The fire starts because the coffee pot dries out, a person sneaks a cigarette and snuffs it out or someone leaves four inches of paper on a laptop.

If a fire starts on a roof, it’s not unusual to find workers doing repairs or replacing equipment. “So if you’re doing renovations, you have a different ignition source but it’s still the human element,” Capko says.

One indication of the importance of the human role in causing fires is the relative rarity of fires in warehouses compared to offices, hospitals or colleges. Warehouses may well contain combustible material, but there are fewer warehouse fires than one might expect. One reason: There are few, if any, people in a warehouse to start a fire, Capko says.

Indeed, the number of people in a building, and the types of things they are likely to do in the building on a regular basis, are important gauges of the risk the building is facing. In commercial buildings, fire hazards are multiplied because of the number of people and things that can start fires, says John Drengenberg, consumer affairs manager for Underwriters Laboratories. One hotel, for example, might have 100 kitchenettes with 100 microwave ovens. Statistics show that the most common reason for microwave fires is someone leaving popcorn or potatoes in longer than needed, Drengenberg says. “It boils down to user issues and not appliances,” he says.

To minimize the risk that people will inadvertently start a fire, education is important. In facilities where flammable liquids are used, for example, training is one of the most important steps that can be taken to lower or limit the risk of fire. Building occupants who use or come into contact with those liquids should know how to store and dispense them, says Chris Jelenewicz, an engineering program manager with the Society of Fire Protection Engineers. Different facilities require different approaches. In an office, there should be rules about the use of coffee makers, for example.

“Another thing to think about is the fact that equipment malfunctions and that can lead to a fire,” Jelenewicz says. “A building owner should have good, sound, safe maintenance procedures because upkeep on that equipment can go a long way in preventing fires.”

In Case of Fire

Although the best way to minimize fire risks is to prevent fires in the first place, facility executives shouldn’t limit fire-risk management efforts to factors that ignite a blaze. Once a fire has started, the way that people respond can literally be the difference between life and death. To manage fire risks, it’s just as important to understand how people behave when there is a fire as it is to know the role that human beings play in starting fires.

For example, it’s not uncommon to see people fighting a fire waiting to take action until they know where a fire is, or waiting to act until they have more information than just the sound and sight of a fire alarm. Whatever the reason, people seem to have a natural predisposition to wait. By delaying, occupants increase the risk that they will come to harm in a fire. “Facility executives need to understand that people do these things,” says Jelenewicz. “Every second counts in terms of getting out of buildings.”

Failing to get out of a building is a greater risk than ever. A recent study by Underwriters Laboratories found that when residential smoke alarms sounded 30 years ago, occupants had 15 to 17 minutes to get out safely. Now they have just three to four minutes, Drengenberg says. The same can be said for exiting a commercial or institutional building: There’s less time than there once was.

The biggest reason, Underwriters Laboratories found, is that today’s houses have more synthetic materials than they did 30 years ago. That’s also true for non-residential buildings, Drengenberg says. The polyurethane foam in furniture, such as mattresses in hotels, is one example. When they catch fire, synthetic materials burn hotter and faster because of their carbon structure, Drengenberg says.

The fire five years ago at the Station nightclub in West Warwick, R.I., provides a tragic example of the risks posed by the greater volume of synthetic materials. Polyurethane foam used for sound insulation in the nightclub was one of the major contributing factors in the deaths of the 100 people when a fire broke out, Jelenewicz says. The foam easily catches fire and the blaze spreads quickly, he says.

Emergency Plan

Headlines in the past few years — from terrorist attacks to natural disasters and power failures — have put emergency response plans at the top of the agenda for many facility executives. The scope of those plans can be broad, reaching complex and vital issues of business continuity. But in the development of sophisticated emergency response plans, facility executives should never lose sight of the highest priority: protecting occupants.

The emergency plan should be built on a solid understanding of the occupants of a building and the way they will respond to a fire. The plan should be appropriate for the facility’s occupants and allow them to exit a building easily and quickly. All occupants should be familiar with the sound of the fire alarm, the location of the exits and the paths to those exits, says Robert Solomon, assistant vice president for building and life safety codes at the National Fire Protection Association.

Occupants of a building may only be familiar with the main entrance door and consequently not be aware of other ways to exit the structure, Jelenewicz says. A building’s employees and occupants should know all the ways to get out, as well as how the stairwells and doors work so that they don’t get trapped.

Contract employees should be treated just like in-house workers when it comes to responding to a fire, Capko says. That means a facility’s cleaning staff, for example, should know and abide by all safety and security rules. “Any employee should know how to pull the fire alarm or pick up the phone and dial 911,” Capko says.

As unpopular as they are, fire drills are an essential step in the process of managing fire risks. Drills are the best way to try to ensure that occupants respond appropriately if a fire breaks out. Fire drills should be conducted on a regular basis, keeping in mind that many occupants — recently hired employees, for example — may not have been in the building the last time a fire drill was conducted, Capko says.

Facility staff also need to know which events will trigger a full-scale evacuation and which won’t, Solomon says. In a typical office building, occupants are moved off the floor where the fire is burning, as well as off the floors immediately above and below. A larger evacuation can then be implemented if needed.

Another critical element of an emergency plan is ensuring that the facility staff understands what measures should be taken for occupants and visitors who have disabilities. “That segment of the population can’t be overlooked, and planning is absolutely essential,” Solomon says.

Facility executives should reevaluate their emergency plans after a renovation, no matter how small or large. If an office space is converted into a large conference room, more exits from that room might be needed, Jelenewicz says. Adding hazardous materials, such as flammable liquids, to an area may mean changing a sprinkler system so that it’s more powerful, he says.

Facility executives are very important stakeholders in a fire protection program, Jelenewicz says. But putting together an emergency plan is only part of the facility executive’s responsibility. Equally important is making sure the facility is following those plans. Even the best plan won’t do any good if it’s just sitting on a shelf.

What Starts Office Fires?

Figures are from the National Fire Protection Association’s Fire Analysis and Research Division report titled “U.S. Structure Fires in Office Properties” released in May 2007. The report looked at the leading causes of fires between 2000 and 2004, the latest years available.

|

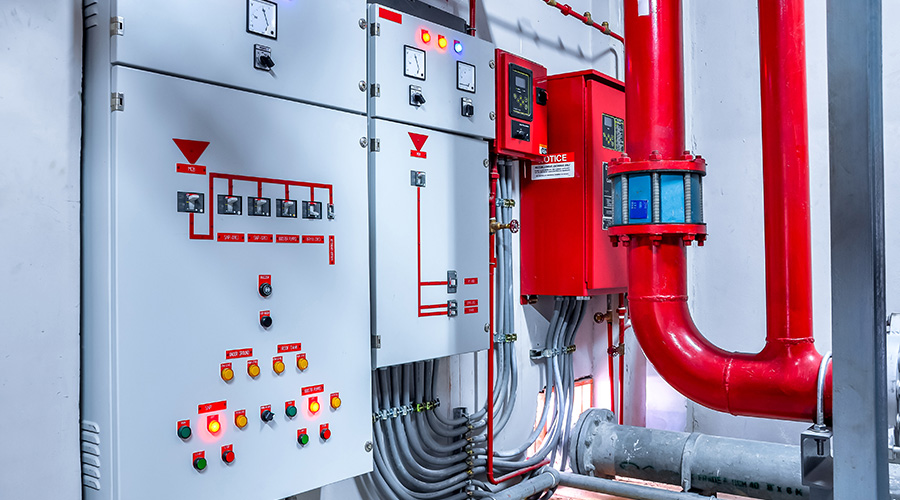

Fire Safety: Keeping Building Systems in Shape

One of the most important steps that facility executives can take to address fire risks is to properly examine and maintain all of a building’s fire safety systems, from sprinklers to emergency exits, on a regular basis, according to Robert Solomon, assistant vice president for building and life safety codes at the National Fire Protection Association. Some of the systems that should be regularly checked include:

Automated sprinkler system. Monitor and check the position of the main control valve for an automated sprinkler system. A closed valve is one of the most common and overlooked risks, Solomon says. A floor control or the main valve for the whole system may have been shut for preventive maintenance and never turned back on. “Make sure it’s open,” says Solomon.

A particularly troublesome but easily remedied matter is not having enough clearance below sprinklers. A copy room, for example, may be filled high with boxes of paper and supplies. Solomon warns that there must be a minimum of 18 inches of clear space beneath a sprinkler so that the water stream can reach the area that is supposed to be covered.

Fire alarms. The manual pull alarms should be easily visible and not blocked by items such as storage boxes or desktop computers, Solomon says. Each alarm should be tested annually when occupants aren’t in the facility, he says. More frequent visual inspections should supplement the annual inspection; the idea is to look for indications that an alarm isn’t working.

It’s crucial that a control panel recognize when an alarm has been pulled and that it activate the appropriate audible and visual alarms either in the entire facility or on a specific floor or floors, he says.

Fire doors. The main functional issue with fire doors is ensuring that they close and latch properly, Solomon says. If a fire door gets used regularly — perhaps it’s between a hallway and a stairwell — monitoring it is particularly critical because of the heavy use.

The doors must also be inspected to make sure that they haven’t been compromised. A damaged door could become a safety hazard.

A fire door with a glass panel is tested with the panel intact, Solomon says. Even a small crack in the glass panel could allow some convective heat to pass through, and that could lead to the fire spreading to the other side of the door. Making changes to a fire door once it’s installed, such as hanging a sign on it, can affect the door’s performance. “That door is tested under very specific circumstances,” Solomon says. Any field modifications can impair the intended performance.

Exit signs/Emergency lighting. The key to exit signs is making sure that they’re properly illuminated. In a health care facility such as a hospital, having even a single bulb burned out will be noted in a report by a state health agency, Solomon says.

Emergency lighting is sometimes tied into an emergency generator, so there needs to be periodic testing of that generator, Solomon says. Emergency lighting is crucial to keeping a building’s occupants calm. The emergency lighting either failed to operate or was non-existent at the World Trade Center in New York after the 1993 bombing, and therefore it took some people up to eight hours to exit the structure, Solomon says. The issue was addressed by the time of the 2001 attacks.

Fire barrier walls. Poke-through penetrations are the main concern with fire barrier walls. When a building is retrofitted with one-half-inch diameter DSL cables, for example, 2-inch holes are drilled through walls by people who have no idea what the purpose of the walls are, Solomon says. “Those breaches mean you’re no longer being properly protected,” he says. “Again, the integrity is compromised.”

|

Desiree J. Hanford is a freelance writer who spent 10 years as a reporter for Dow Jones. She is a former assistant editor of Building Operating Management.

Related Topics: