Fire-Safety Systems: Debunking Myths, Anticipating Trouble

OTHER PARTS OF THIS ARTICLEPt. 1: This Page

Note: This is the first part of a two-part article on the inspection and maintenance of fire-safety systems. The second part appeared online in March 2014.

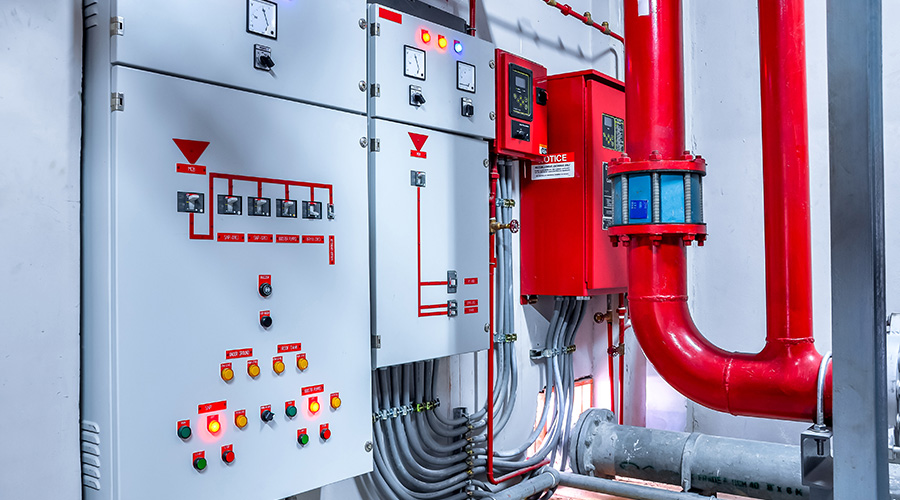

Fire-protection systems in institutional and commercial facilities generally have long performance lives, provided they were designed and installed properly. But to be fully effective, fire-protection systems require more than that. They require that maintenance and engineering managers implement an inspection and testing program that ensure both performance and code compliance.

But to achieve these goals, managers need to avoid several obstacles — namely, misconceptions related to fire-safety systems and common system trouble spots.

Testing, testing, …

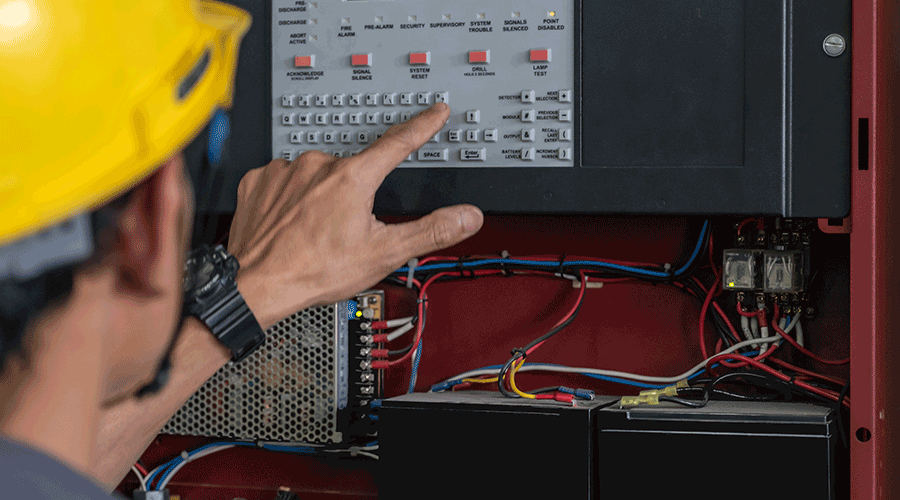

As with many other facility systems and components, proper inspection and maintenance requirements often combine with misinformation and misunderstandings to undermine managers’ best efforts at efficiency and safety. Consider the issue of system inspections under NFPA 25, Standard for the Inspection, Testing, and Maintenance of Water-Based Fire Protection Systems.

“The No. 1 issue or myth that we see is that owners believe that if they’re having their sprinkler systems inspected annually for NFPA 25, they believe it’s going to expose all the problems in their systems,” says Christopher Culp, P.E., who is vice president and a fire protection engineer with Henderson Engineers Inc. In fact, though, that is not the case.

“What most owners don’t understand is that NFPA 25 is only supposed to verify that a system is operating correctly, that the components that are there are in good working order.

“Are the valves opening and shutting? Are the pipes free of corrosion? Are the sprinklers free of paint? But they might not understand that if there is a design issue or an insulation problem, (the inspection) won’t expose those things.”

Culp offers the example of a building with a dry-pipe system with a pipe that runs outside the building.

“If that pipe isn’t pitched properly, it doesn’t drain,” Culp says. “The condensation that forms in that pipe won’t go to the drum drip to be drained out. It will collect somewhere and freeze and break. Your NFPA inspections or annual inspections will not expose those (problems). They’re not designed to, and that’s not the intent of NFPA 25.

“A lot of owners often say, ‘I have my annual (inspection). Why do I need you to help me figure out my problems?’ ”

Common fire-safety issues in specific facilities

Even if managers oversee proper inspections of fire-safety systems, problems can arise that impair the systems’ effectiveness and endanger occupants and operations.

“There are common problems that we see when we do remodels or takeovers of existing buildings, problems that we see pretty much everywhere,” Culp says. As an example, he cites system failures that result from valves that are closed or partially closed.

“Those are usually pretty easy to figure out,” he says. “But we do run across buildings where we walk in and find valves shut. Painted sprinklers, painted smoke detectors, painted heat detectors — those aren’t supposed to happen, but we find them, (as well as) alarm systems where the horns are taped over because it’s annoying (occupants) when it’s going off.”

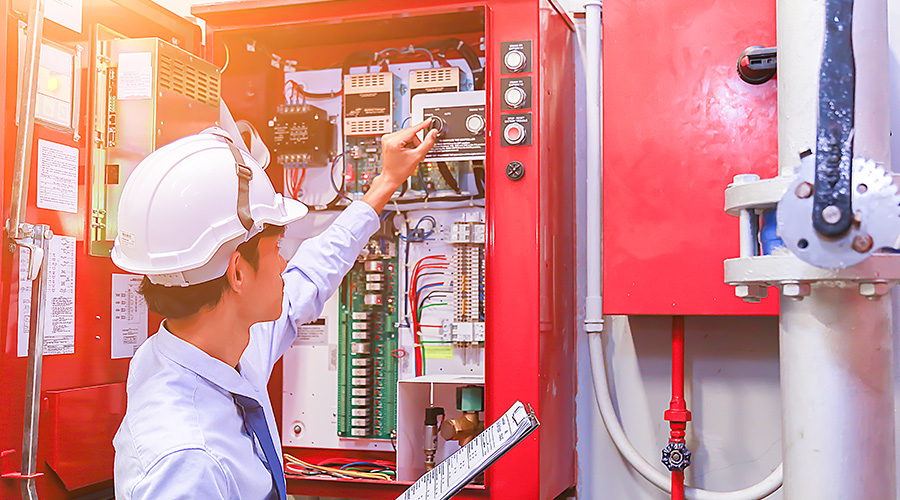

Health care facilities, given the complexity of their operations, can present managers with unique fire-safety challenges.

Culp says these facilities “have a lot of attic spaces that have sprinklers, and a lot of these spaces don’t have insulation over the piping the correct way, or they might not have heating in all the concealed spaces. A lot of health care facilities are sort of residential in appearance, and because of that, we see a lot of issues with attics.”

Fire-safety issues in K-12 buildings tend to fall into a different category — vandalism.

“Here, you’re talking about user issues — vandalism and intentional damage, the proverbial kid in the gym who’s trying to throw a football and knock the sprinkler out or something,” Culp says. “If the buildings have pools, these areas have a lot of corrosion issues if they don’t use the correct pipe or sprinklers. The caustic chemicals will corrode the brass and steel very quickly.

“You also might have insulation issues in older buildings. Some of the piping might be exposed, and if so, it’s a target because maybe some of the boys want to use it as a pull-up bar.”

Commercial buildings, because of the unique and often changing nature of their operations and activities, tend to develop still different problems.

“Usually, we see that the repurposed spaces aren’t designed for their current use,” Culp says. “For example, you have a break room. But the company has grown, so maybe the break room is now a storage room. So you have what used to be a light-hazard space, and the design level has increased. That becomes a design issue, and from a fire-protection standpoint, that’s really something (managers) have to watch for.”

Related Topics: