Blazing a Path: New Technology, Design Approach Move Fire Safety Forward

The objective of fire and life safety systems installed in a facility remains the same as ever: to protect the occupants and facility in the event of a fire or other emergency. That isn’t going to change.

However, advancing technology and changing building designs are prompting some carefully chosen modifications and enhancements to these systems. For instance, some fire alarm and notification systems now use digitized voice technology, either instead of or in addition to an alarm. The voice provides additional directions to occupants during an emergency. Performance-based design of fire and life safety systems, while still used in a minority of facilities, is becoming more recognized by building code officials. Changes like these affect the way facility executives maintain building systems.

One shift occurring in data centers and other critical facilities is the decision by some facility executives to install fire detection systems that actually exceed code requirements, says Jim Carrigan, associate partner and supervising engineer for fire and life safety with Syska Hennessy Group. “Driving this is concern about terror attacks,” Carrigan says. “People are concerned about critical infrastructure facilities, such as hospitals and brokerage houses or other facilities where high volumes of data are processed.”

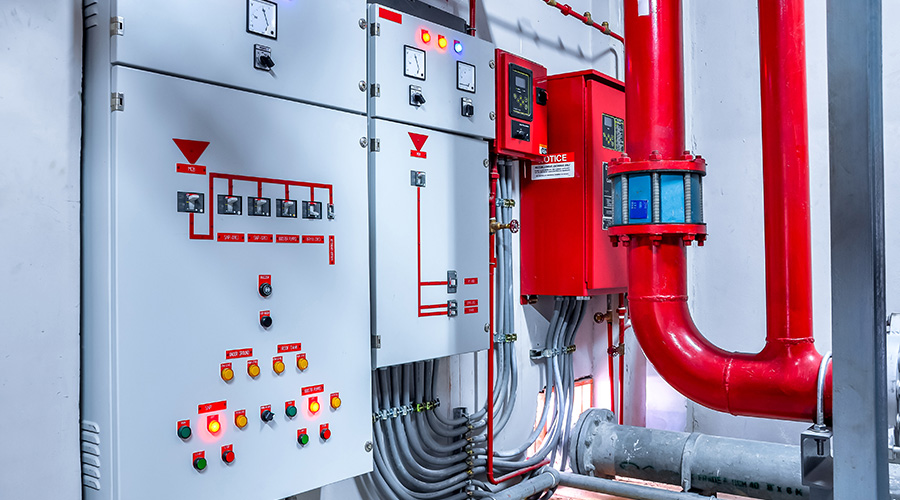

Carrigan has seen more facility executives install what are referred to as “pre-action systems.” These provide two levels of protection, such as both a smoke detection system and a sprinkler system. This often exceeds code requirements, as many codes don’t require a smoke detection system if the building is sprinklered.

Fire suppression technology also is advancing. “Manufacturers of fire suppression systems are always coming up with new sprinklers to address unique high-challenge fire scenarios,” says Frederick Mowrer, associate professor of fire protection engineering at the University of Maryland — College Park. One example is what’s known as early suppression, fast response (ESFR) sprinklers. These spray higher volumes of water directly on a fire to extinguish it. In contrast, other sprinkler systems are designed to spray water in the general vicinity of the fire in an effort to keep it under control until the fire department arrives.

Another example is the K25 sprinkler. This sprinkler has a large orifice and can spray more water at a lower pressure. As a result, it may be possible to get by without an expensive fire pump, Mowrer says.

A growing number of companies are installing fire extinguishing systems that use gaseous substances, rather than water, to control or extinguish fires, says Carrigan. These are most often used in areas with expensive computer equipment, as they eliminate the risk that water will spray onto the equipment. However, the systems are expensive and require extra space to store the cylinders that house the gases. As a result, facility executives are unlikely to use them to protect an entire facility.

Advances in Technology

Fire alarm system technology also is moving forward. Some systems now are able to indicate where the fire actually is occurring, says Alex Kline of RJA Associates.

In addition, a growing number use a voice that lets occupants know what the emergency is, where it is occurring, and how they should exit, says Chris Jelenewicz, engineering program manager with the Society of Fire Protection Engineers. “People like more information when it comes to evacuating.”

It’s important to remember that these need to be properly designed so that the communication is clear. The system shouldn’t provide so much information that it confuses people.

One technical tool that currently is in the research and development stage involves video systems that can detect fire, says Mowrer. The systems, which could be part of a video security system, would analyze different elements of a fire, such as its temperature and the amount of smoke it is producing.

Also under development are tools that would monitor the “health” of buildings during a fire in order to determine whether it’s prudent to send in firefighters, says Mowrer. The systems would measure temperatures at different locations in the building and examine the manner in which the fire is spreading, among other factors.

Before a facility executive implements a new fire and life safety technology, it is necessary to get approval from code officials, says Daniel W. Murphy, senior vice president with Environmental Systems Design. In some cities, fire department officials actually may not want systems that exceed the code, as their own systems and procedures are designed to work within the code. Changes that a building owner makes to the safety system could hamper their ability to respond quickly and effectively in an emergency.

Performance-based Design

For most facilities, incorporating fire protection by following the applicable code requirements will suffice. For a small minority — approximately five to ten percent, estimates Kline — the code doesn’t work very well. It may be that the building design isn’t covered by the code, or the way the building is used makes it difficult to apply the code.

For example, a library may house a rare book collection. If a fire were to start in that area, library officials would want to contain it away from the books, says Jelenewicz. The code may not address this particular scenario.

In those cases, facility executives may move to what’s known as performance-based design. “You identify the level of safety that needs to be provided,” says Jelenewicz. Then, all stakeholders involved with the building work with code officials to determine how to best meet the fire protection goals.

For instance, the code may require a certain number of smoke fans in an atrium area and mandate that they provide a certain number of air changes per hour, Jelenewicz says. In a performance-based approach, the objective might be to ensure that the smoke layer doesn’t descend to lower than six feet above the highest occupant in the building. The system would be designed to meet this goal.

Performance-based design is also known as equivalency, says Milosh Puchovsky, principal fire protection engineer with the National Fire Protection Association. If the code doesn’t apply to a particular building, the facility executive can work with code officials to develop another method of protecting the building that still meets the intent of the code and provides a safe environment.

Performance-based design means applying engineering criteria and knowledge to solve fire and life safety issues, says Murphy. The team working on the design will try to determine, using computer tools and engineering methods, how a fire might progress through a building and how the sprinkler and alarm systems might respond. Based on this information, they’ll try to determine the most effective ways to prevent, contain and suppress any fires that may occur, and how to move the building’s occupants to safety within or outside the building.

Performance-based design is most often used with multilevel atriums and one-of-a-kind facilities. Many of the casinos lining the Strip in Las Vegas, for instance, use fire safety systems that were developed using performance-based design.

Kline recently worked on a high school in Dallas that features open spaces and large atria that are inter-connected. The code didn’t address the atrium design, so he and school district officials worked with the code authorities to develop an appropriate fire and life safety system. Using three-dimensional computer modeling, Kline and his colleagues analyzed the building to understand how a fire might spread, how it could be controlled, and how students and other occupants would exit. Based on the analysis, the team installed exhaust fans to control smoke and glass curtains to keep smoke from spreading, among other steps.

Advances in computer technology make the use of performance-based design more feasible. “Now we have the analytical tools available to address expected fire scenarios and their consequences in more detail,” says Mowrer. These computer models can calculate how fast a fire is likely to burn, and the amount of smoke and carbon monoxide it is likely to produce.

While performance-based design is the appropriate choice for some buildings, experts agree that it’s unlikely to be used for more than a small number of systems. First, performance-based design can only be used when the authorities having jurisdiction allow it, says Murphy. “They may or may not consider it.”

However, if the proposal makes sense, many code officials will consider it, although they may ask for changes to specific parts of the plan, says Kline of RJA. “Typically, code officials are receptive.”

The performance-based design process requires additional time to design and engineer the system, says Puchovsky. “Engineering costs go up because you’re not doing a cookbook approach.” However, the approach may reduce the installed cost of the system as well as its life-cycle cost.

Added Responsibilities

In addition, performance-based design can expose the facility executive to greater liability. With a prescriptive system, determining whether the system meets code is fairly clear-cut. In a performance-based system, all stakeholders need a clear understanding of the performance expectations, Mowrer says. As a result, thoroughly documenting the requirements of the system is critical.

It’s essential that the system continue to meet the initial design intent even if changes occur in the building. “You have to maintain a lot of features differently from what you normally do,” says Eric Rosenbaum, director of architectural and engineering services with Hughes Associates. For example, in a building with a large, multi-level atrium, the performance-based design may assume that no tenants with high fuel loads will be located at the base of the atrium. If over the course of the life of the building the atrium tenants change — a restaurant comes in, for example — that could potentially raise the fuel load and cause fire safety problems. In a building that uses performance-based design, facility executives should have an operations and maintenance manual that identifies the features maintained in a manner that’s different from what is typically done.

In light of these challenges, performance-based design most likely will continue to be reserved for situations in which the codes don’t cover the specific use or design of a building.

Planning Process

Facility executives should take several steps when they’re involved in the development of a fire and life safety system. At the start of the project, it makes sense to consider the impact of other renovation or building projects that may be going on at the same time, says Carrigan. “You can’t design in a vacuum.”

For example, Carrigan cites a project on which smoke detectors were being installed in patient rooms in a health care facility. In health care facilities, it is difficult to take rooms out of service for construction, due to the financial impact and disruption of patient care. When the rooms are occupied, contractors can’t just enter and begin cutting into the walls or removing ceiling tiles. Infection and dust control procedures must be employed.

It was only by accident that Carrigan learned that the facility also was doing some plumbing renovation work that affected all patient rooms. He suggested that the patient room smoke detector replacements be integrated into the plumbing renovation project, which was ongoing. This meant that the patient rooms were disturbed just once instead of multiple times.

The majority of the smoke detector rough-in work was completed off-site, allowing the new detector base, associated electrical back-box, ceiling tile and new cabling to be pre-assembled. When the patient room was taken out of service for the plumbing renovation, the electrical contractor was permitted to install the new smoke detector components. The actual smoke detector device installation could then occur any time thereafter by simply fitting the detector onto the previously installed detector base.

Remembering the Basics

Properly maintaining a fire and life safety system is critical, of course. It’s also required by code, and in some cases, required by the insurer of the facility. Many times when a fire occurs in a sprinklered building, it’s because someone has compromised the ability of the system to work, Murphy says. Some jurisdictions and insurers require maintenance and testing be performed by an independent third party.

Finally, it’s advisable to “keep the systems simple,” says Rosenbaum. For instance, if several tenants in a commercial office building decide to install their own fire and life safety systems, maintaining and ensuring the integrity of the various systems becomes much more difficult. “The simpler you keep it, the more likely it is the system will work.”

That is key, given the role that these systems can play in an emergency. “These aren’t systems that are used every day, but when they are needed, they’ve got to operate flawlessly,” says Murphy.

Karen Kroll, a contributing editor for Building Operating Management, is a freelance writer who has written extensively about real estate and facility issues.

Related Topics: