Fire Safety: Finding the Weakest Link

The majority of fire-related losses can be prevented if fire protection measures perform as intended in an emergency.

Facility executives can improve the fire safety of buildings by understanding both how and why individual systems work, and how and why systems work together.

“The most important thing to help improve fire safety is to understand how all the systems in a building work: The alarms, the means of egress and passive building systems like fire doors and walls and dampers,” says Chris Jelenewicz, engineering program manager for the Society of Fire Protection Engineers. “Facility executives must understand how they operate. All of the systems have a common goal and that is to protect people and property. They work together as one integrated life system. Like a band, they all do different things, but they play to the same beat. If the systems don’t work together, they could actually make matters worse.”

Of course, facility executives should make sure that the systems are working properly in the first place. Individual schedules and checklists for maintaining and servicing these critical systems for each building should be developed and implemented.

“Each checklist for each facility is different,” says Keith Domagala, operations vice president and engineering manager for Affiliated FM. “Facility executives need to determine what is different about each facility and develop a plan on what to do.”

The timing of inspections should be in accordance with local codes and standards, but there are some things codes and standards don’t cover.

A closed sprinkler valve is the most common cause of failure in a sprinkler system. The valve gets turned off for maintenance and isn’t turned back on, or a building worker twists it for some reason, not knowing whether it’s open or closed.

“If the valve to a water fountain is shut off, as soon as you go to get a drink, you know something is wrong,” Domagala says. “But if the sprinkler valves are shut off, you don’t know it until there is a fire, and that’s the danger.”

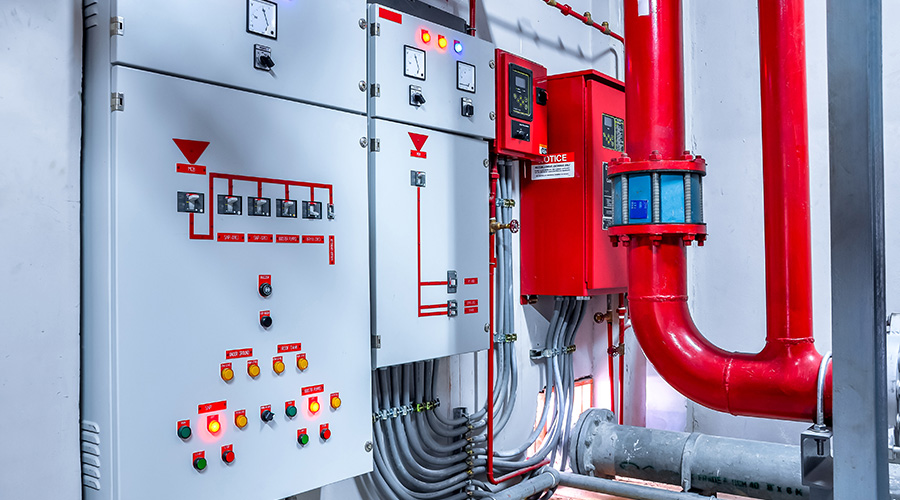

Valves, including those that supply water to the building, should be checked weekly to ensure they are open, and a full flow test should be conducted at least yearly, experts say. Pumps that bring water into the building should be checked and maintained as well, says Gary Keith, vice president of building and life safety for the National Fire Protection Association. The fire pumps should have access to an adequate water supply and ready access to a fuel supply, whether diesel or electric.

A main drain test should be included on the checklist. The five-minute test measures the static pressure and then measures the pressure of water flowing. The purpose is to determine whether there are any obstructions, such as broken or frozen pipes, in the system.

This test is particularly important in warm regions that experience occasional cold weather because freezing precautions usually aren’t routine.

Fire alarm systems and their audibility should be regularly tested as well. This is mainly important with voice fire alarms. Use fire drills and even false alarms to determine whether occupants can clearly hear the directions that are being given.

“When it comes to fire alarms, evacuation information is most important,” Jelenewicz says. “Building occupants need to know what they’re supposed to do.”

Control panels should be tested as well. Control panels provide valuable information, such as pinpointing closed valves and other problems before an emergency occurs.

Facility executives also should walk the exit routes to make sure no exits are blocked or locked. Historically, blocked exits are the cause of most fire-related deaths in commercial buildings, Jelenewicz says.

Security vs. Fire Safety

In the aftermath of 9/11, security measures are more frequently interfering with life safety systems, Keith says. Emergency exit doors that lock people in the stairwell and only allow people to exit at the bottom are one example.

“What if the fire is below? What if they need to evacuate up? Any time you change security measures, you need to see how it affects life safety,” Jelenewicz says.

“Post-9/11 security improvements have resulted in unintentional barriers to fire and life safety,” says Keith. “They’re restricting movement in a building. Facility executives are looking at keeping people out, and sometimes these systems work too well. There needs to be a proper balance between security and fire safety.”

Jelenewicz agrees. “Security and life safety have common goals, but if security is not coordinated with life safety, then it becomes a hazard. There needs to be procedures to make sure exit doors aren’t locked or blocked.”

One way to solve this problem is to connect the locking system of all doors in the facility to the fire alarm system so that all safe routes offer unobstructed egress and ingress during an emergency.

All exits, exit ways and discharge points must have adequate and functioning lighting. This means the lighting system must be checked regularly.

Facility executives also can improve the safety of the building by exercising common sense. Stairwells and electrical closets should never be used for storage and flammable materials should be stored away from all heat sources, says Dan Gemeny, chief engineer for RJA.

“There seems to be a huge problem with inattention to the storage of combustibles and flammable materials in the most risky of places,” Gemeny says. “Some maintenance crews even store trash in the stairwells. They think, ‘Out of sight, out of mind.’ They wait until the fire department comes and babysits them to change the situation. It’s a risky behavior.”

Facility executives should also develop policies for predictable hazards.

For example, hot work, such as cutting, grinding and welding, is often a cause of fires, according to statistics. Facility executives should develop policies for contractors and maintenance crews to follow. The process should include provisions for someone to stand by on fire watch to make sure stray sparks are extinguished immediately. The procedure should require that a fire extinguisher be within reach at all times. All combustibles should be removed from the area. If that’s not possible, they should be covered with a welding blanket. Removing significant ignition sources reduces the chances of fire.

When hiring a contractor, the first question to ask, Domagala says, is, “Can you do what you need to do without doing hot work?”

If there is no way around hot work, then the facility executive must manage the project directly. Don’t leave it to the contractor to oversee the work.

“Somebody has to manage the work and take responsibility to make sure contractors are following these safety practices,” Domagala says.

The facility executive also should focus on contingency planning.

“Emergency contingency planning covers unforeseen circumstances, such as flood or wind or fire,” Domagala says. “Or it can be as simple as a key piece of equipment breaking down. You need contingency planning so when something happens you can do the right thing at the right time.”

The contingency plan should cover events that seem unlikely but are still possible. For example, what happens if a key fire protection or life safety system fails in the middle of a crisis? What if a fire starts while a system is down for maintenance? What if a fire breaks out during another disaster, such as a hurricane?

“Having thorough plans and practices and doing the right thing at the right time is the difference between a distraction and a disaster,” Domagala says.

As part of the preparation process, facility executives should conduct an orientation for the local fire department, Keith says.

“Describe what systems are available and have joint documentation so when something happens, everyone has basic information at their finger tips.”

Know Thy Building

Finally, facility executives should know their buildings inside and out. What construction components provide for fire and life safety and what components hinder it? What are the limitations of these systems?

Facility executives must make sure the building is designed for all the hazards it faces, and understand that if building use changes, then the hazards change. Sprinkler systems often are designed for a specific hazard. Warehouses require more water than office buildings. A smoke management system designed to accommodate an open atrium might be inadequate if a restaurant is added to the space.

“Facility managers are the only ones to think about these things,” Jelenewicz says. “It’s not their responsibility to change the design to make it safer, but they should know when a problem exists and then make sure the design is changed.”

Construction materials must be documented as well, Domagala says. “Some construction materials burn faster than others.”

For example, plastics are commonly used in construction because they are easy to clean and sanitize. However, some types of plastics burn more readily than others and once set ablaze are difficult to control with ceiling sprinklers.

Materials should be tested and approved for certain types of occupancies.

“Test the materials to know what you have,” Domagala says. “Then look at the loss history of those products. Some products have better performance than others.”

Keeping Up With Changes

Facility executives also should know where the fire walls are and what shape they’re in, Keith says. A fire wall with a hole in it won’t stop a fire.

Facility executives also should be aware of all the previous uses of the building and whether the original fire protection systems used a performance-based design.

These buildings may be dependent on one specific fire safety system compatible with the original use. If the building changes hands and uses, the performance-based design may no longer be suitable for the new application. Unfortunately, this information isn’t always communicated to the new owner.

“Building systems are documented during design and construction, but future owners might not be aware of those limitations or criteria, so it does not get incorporated into their changes,” Gemeny says. “There’s a chance that information gets lost when buildings change hands. And that’s important because performance-based buildings require a more engineered review of changes. Or systems may have to be maintained differently because one system is more critical in the performance-based design.”

One solution is to incorporate redundancy into the original design “and live with cost and inefficiency to make the building more robust in the future,” he says.

The bottom line of all these suggestions is to prevent loss. The majority of losses are preventable, Domagala says. “It’s easier to prevent loss than to recover from the aftermath.”

Lynn Proctor Windle, a contributing editor to Building Operating Management, is a freelance writer who has written extensively about real estate.

Related Topics: