The 1980s: When Office Spaces Were King

From cubicles to personal computers, facility management in this decade was all about being flexible

By Dan Weltin, Editor-in-Chief

To celebrate Building Operating Management’s 70th anniversary, we are taking a look back at each decade. Check out the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Here we are looking at the 1980s.

As the 1980s began, spiraling construction costs, inflation and high interest rates, coupled with tighter regulations and stricter building codes, dampened the outlook for new construction. Instead, it was more cost effective to retrofit existing buildings to modernize and conserve energy. Each year, more money was spent on retrofitting and by decade’s end, remodeling expenditures surpassed new construction spending, totaling $104 billion.

“Bringing old buildings up to modern standards becomes more economically attractive as new construction costs continue to soar,” wrote the Architectural Aluminum Manufacturers Association in a 1981 article.

During this decade, more than 40 percent of the workforce was in an office setting. With new construction slowing, existing office space became harder to rent. There were few vacancies in major cities and building owners upgraded their space knowing they could charge a premium to attract tenants.

The rising costs of leasing helped the concept of the “open office” finally catch on in the United States. Introduced in the late ‘60s in Europe, the West German ‘burolandschaft’ used cubicle partitions to maximize space and privatize work areas without permanent walls. Sound masking and acoustic ceiling tiles were added to help privatize conversations. The concept was originally met with skepticism from U.S. building owners, but by 1984, almost half of all office space employed this technique. Using moveable partitions allowed offices to be flexible with their design as facility managers looked to shrink workspaces to save money on rent or allow more space to be given to new computerized technology.

“Imported from Europe about 15 years ago, the open plan has gradually evolved into a popular design option for American office planners, and has radically altered the appearance of environments that had remained static for years,” wrote assistant editor Sandra McQuide in a 1982 article.

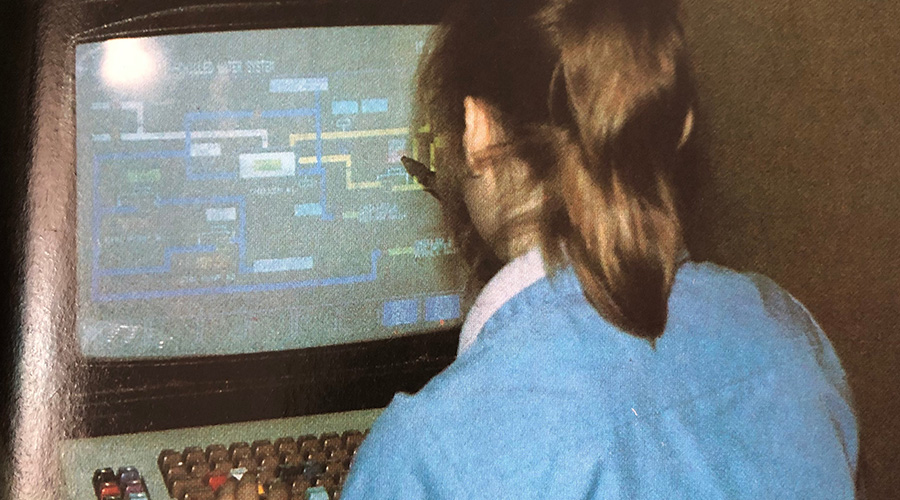

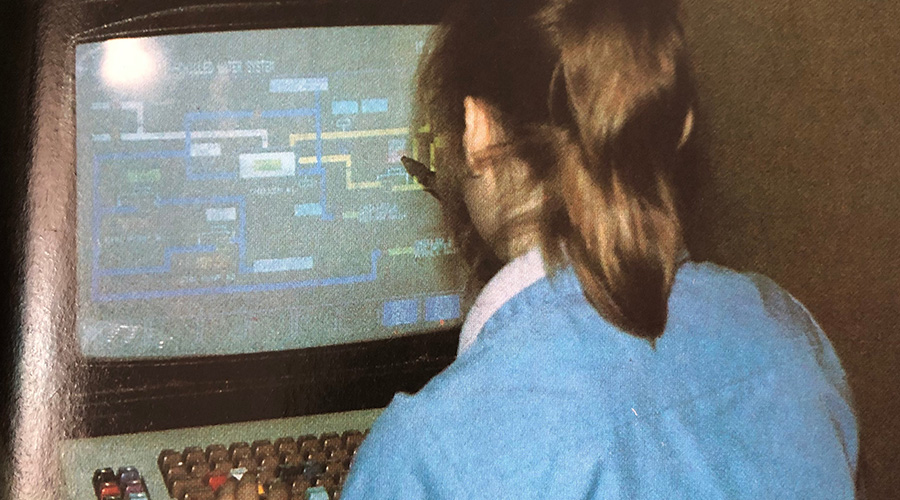

In addition to space management, the increased use of computers in the office world meant new considerations for power generation, wiring, temperature, humidity and even lighting to cut down on glare on computer screens. With technology advancing much faster than before, facility layouts were only being planned for only 1 or 2 years rather than 10 to 15 like it used to be.

Computers were also being used more prominently for facility management tasks and in smaller buildings. For example, in 1983, there more than 2 million commercial buildings in the U.S., but less than 5 percent used a computerized energy management system. However, thanks to advances in computers, it became much more cost effective to utilize an EMS, lighting controls, and building automation systems. In addition, computers were used to improve many more aspects of the facility, including elevators, fire safety, and access control.

The use of so much computerized technology starts to be referred to as “Intelligent buildings” years before people had ever heard of the Internet of Things (let alone the internet).

“To many people, speaking of a building as ‘intelligent,’ seems to be a little strange. Talk of ‘adding intelligence’ to an inanimate object of concrete, steel and glass can be considered a slightly odd endeavor,” wrote Dennis Bauman of Peat, Marwick, Mitchell & Co. In a 1986 article.

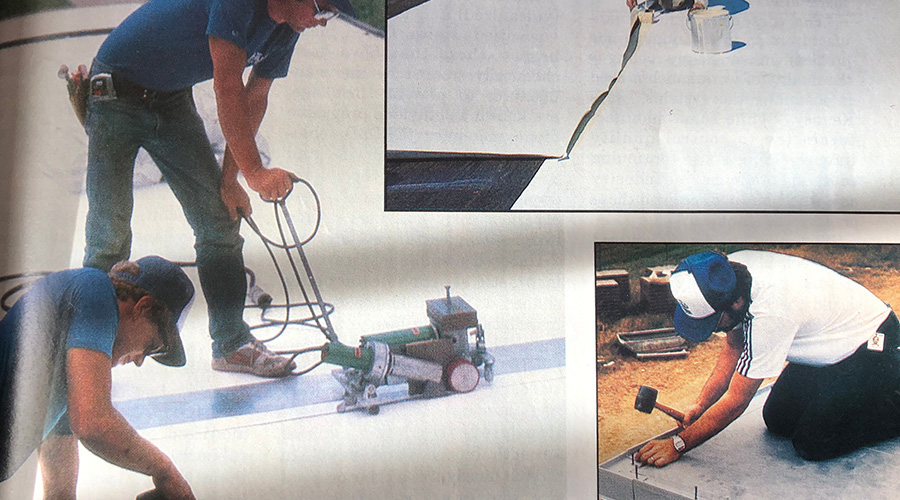

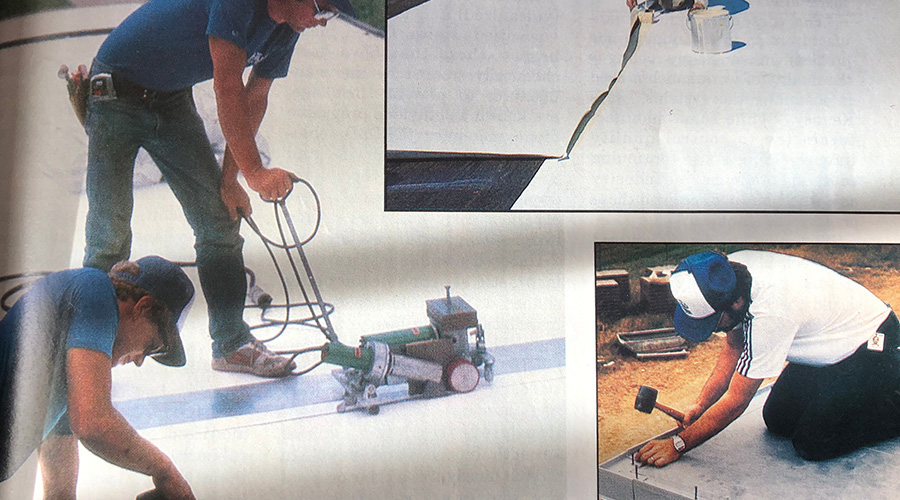

Not all product advancements were computer related. Single ply roofing, introduced in the 1960s and popular in the ‘70s, really picked up steam in the U.S. in the 1980s and is the industry standard for commercial roofing today. Its easy installation made it affordable in a tight economy, energy efficient, durable and long-lasting. By the middle of the decade, more than 40 percent of buildings switch to single ply roofing as more types of products become available, retrofits increase, and the fact that single ply can be retrofitted over built-up roofs (BUR).

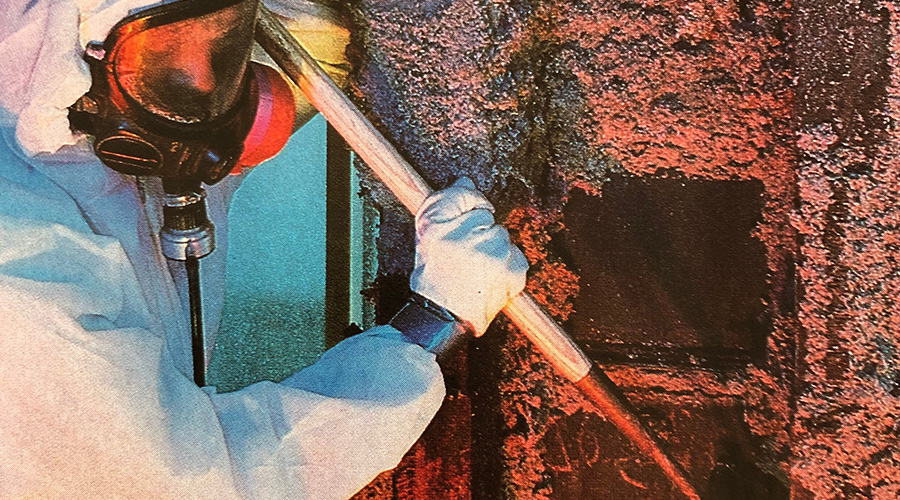

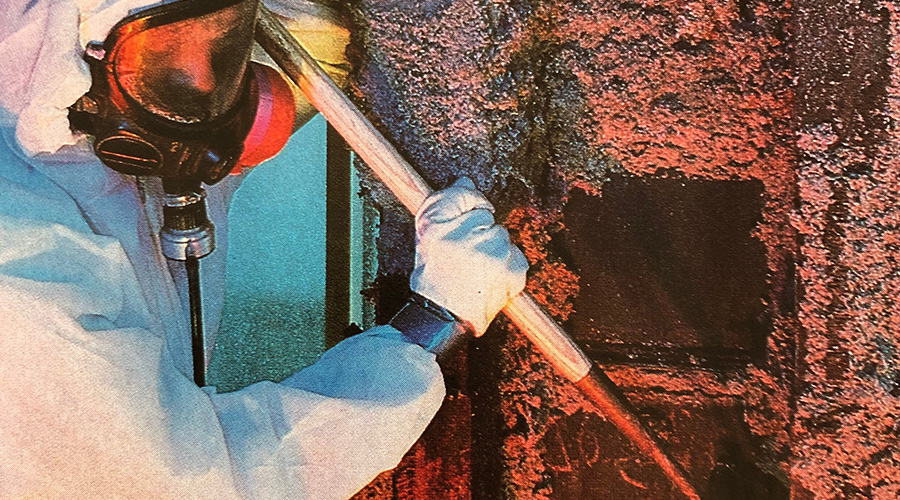

Just like the energy crisis put the facility manager center stage in the 1970s, asbestos spotlighted the role of facility managers in the ‘80s. Most buildings constructed between 1870 and 1975 used boiler, pipe, and ceiling insulation that contained some form of asbestos. In the mid 1970s, asbestos was banned as an insulation material, however, remodeling – which was happening at an unprecedented rate in the ‘80s -- can make it airborne, which is when asbestos becomes dangerous as exposure is linked to lung disease and cancer.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) mandated that public schools be inspected for asbestos in 1982. In wanting a stronger framework for identifying and addressing the problem, Congress passed the Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act effective Jan. 1, 1987. Although this law only applies to public schools and no regulations would ever come to commercial facilities, building owners feared that they were leaving themselves open to lawsuits.

“The very mention of the possible presence of asbestos has caused many building owners to become unduly alarmed,” wrote G.J. Graziano, an industry consultant in 1987.

The EPA estimated that friable asbestos (which can be crumbled or reduced to powder by hand pressure) is in 20 percent of public and commercial buildings or roughly between 700,000 and 900,000 facilities. Building owners could still be held liable if they know or should have known the facility contained asbestos. With prominent properties in Los Angeles and New York selling for millions under assessed value because of the presence of asbestos, asbestos removal is big business and building owners all over the country work to remove as much of the material as possible.

Asbestos wasn’t the only danger lurking in office buildings in the 1980s. During this time, facility managers become more aware of the importance of indoor air quality and sick building syndrome (also referred to as Tight Building Syndrome during the decade).

To conserve energy during the energy crisis of the 1970s, newer buildings were built better and tighter, better insulated with less fresh air circulating, tighter fitting windows and better sealing doors. As a result, contaminants, such as chemicals, fungi, bacteria and dust stay inside. Workers with prolonged exposure feel fatigued, suffer headaches, nausea and hypersensitivity. There is lower productivity, higher absenteeism, increased healthcare expenditures and health threatening effects. Building occupants begin to rethink the concept of smoking in the workplace.

“Complaints about poor air quality usually negatively affect tenant relationships, and if the problems are not addressed, they eventually lower building occupancy rates,” wrote David Eubanks of Climate Engineering Corp. in 1988.

As the decade ends, one third of buildings in the U.S. have poor IAQ. It is believed that the problem will be the “asbestos of the 1990s.”

Dan Weltin is the editor-in-chief of the facilities market. He has more than 20 years of experience writing about facility-related issues.

Related Topics: