Coming to Grips with Sarbanes-Oxley

Documentation and due diligence are among the compliance challenges facing facing facility executives

By now, most Americans have heard at least passing mention of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX). The 2002 legislation, which has received no shortage of press, was introduced as a way to restore investor confidence in the wake of corporate accounting scandals like those involving Enron and WorldCom. By creating a Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), strengthening auditor independence, and increasing corporate management’s accountability for the quality of their organizations’ internal controls, SOX seeks to increase the transparency and rigor of all publicly owned companies’ fiscal management.

SOX is a complicated act with numerous provisions. Of most concern in general, however, is Section 404, which requires an annual assertion from every public company’s management that the internal controls over their financial reporting are effective. Section 404 also requires a statement from an independent auditor as to the quality of the internal controls and the presentation of the organization’s financial statements. As recent headlines attest, boards of directors and top management face severe penalties and even prison time if their statements are found to be false.

SOX was fully implemented in 2004. With a year’s experience under their belts, corporations report that complying with the act, and specifically Section 404, has proven more difficult than they anticipated. Estimates put the cost of compliance for U.S. companies in the range of $5 to $6 billion for 2004.

“It’s really something, the effort that has to be undertaken, starting really deep in the organization, to make sure that these few little notes can be completed,” says Art Elman, vice president, corporate real estate and facilities, ADP.

Facilities departments are no exception. SOX is proving to have significant implications for the way facilities and real estate professionals do their jobs.

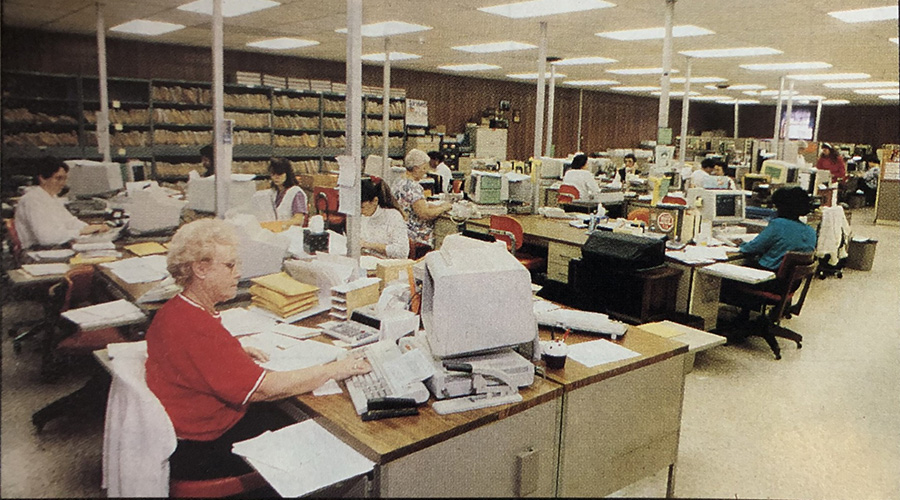

Ask any facility executive what SOX has meant, and one response comes first and foremost: documentation work that never ends.

“It’s not so much that we’ve changed the way we are doing things operationally, as that we now pay attention to the need to prove exactly what we’re doing, again and again,” says Elman.

That is not to say that operations are unaffected by the legislation — among other things, SOX mandates standards for the physical security of data centers and of the power supply to computer facilities; network security; and the existence of data backup policies. And provisions that require corporations to maintain all key records and communications — including e-mail messages — are forcing some organizations to add data storage capacity.

“Corporations that never felt they had to have them before are building data centers or even backup data centers,” says William Kosik, Chicago managing principal, EYP Mission Critical Facilties.

That’s not all. “Floor space is even more squeezed than it was before, because now we have to keep all these paper files,” says Scott Watkowski, vice president of property management, Valley National Bank.

But bigger challenges have come with the need to comprehensively document — from start to finish and via an auditable trail of meeting notes, e-mails, reports, contracts, invoices and receipts — all the activities, projects, expenditures and decisions that have been carried out since time immemorial via informal conversations, ad hoc collaborations and handshakes.

“Tens of thousands of hours within the company, and certainly hundreds within our department, have to be spent documenting every step of every project,” says Elman. “We’re not getting any productivity out of it. Just a lot of paper.”

Complicating contracting

Compounding the administrative headaches SOX presents are the complications it introduces to some of the tasks facility executives are engaged in every day, such as bidding, contracting and capital spending. With its emphasis on ethics, SOX gives corporations new motivation to establish an open and competitive bidding policy and adhere to it closely. While SOX does not contain specific requirements related to bidding, explains Lori Silverstein, internal audit director, Boston Properties, “We believe that the bidding process is an extremely important control and one which mitigates the risk of fraud.”

“The facilities person really needs to understand the thresholds for when you formally bid out work versus when it’s appropriate just to hire someone,” says Arthur Flashman, vice president/controller of Boston Properties.

For better or worse, the selection of a contractor is only the first step.

“You may have begun to feel comfortable with the amount of due diligence it takes to operate responsibly in a post-Sarbanes-Oxley environment,” says Eric Bowles, director of research with CoreNet Global. “But now there’s a second issue: Can you carry this degree of due diligence down your supply chain?”

SOX 404 compliance demands that organizations certify that adequate internal controls govern not only their own operations, but also those of their contractors or service providers. To provide this assurance, management needs to either evaluate each contractor’s internal controls directly or obtain an auditor’s report, known as an SAS 70, attesting to effectiveness of the internal controls. For most organizations, busy enough with their own compliance issues without taking on the investigation of another entity’s controls, the latter is the only reasonable option. But obtaining the SAS 70 presents its own challenges, especially if the contractor is not contractually obligated to provide it, or if it is a private company and therefore not legally obligated to comply with Sarbanes-Oxley itself. For facility executives accustomed to vetting contractors on the basis of their qualifications and price, this means adding a new question to the mix: Is this prospective partner SOX-ready?

“Sarbanes-Oxley is having a ripple effect,” says Boston Properties’ Silverstein. “Public companies are asking third-party management companies — even those that are non-public companies — to implement similar controls to those they themselves are required to have.”

For those firms, 404-readiness could become a marketing tool. “There could be an interesting competitive advantage for those who embrace it early and market that,” says Kurt Padavano, chief operating officer, Advance Realty Group and vice chairman of BOMA International. “Public companies will look more favorably on doing business with private companies if they are following the rules and standards the public companies are being held to.”

While undeniably a headache, the process of obtaining adequate documentation of a contractor’s internal controls is critical: Deloitte has identified the inability to evaluate and test controls over outsourced processes as one of the top ten threats to corporations’ Section 404 compliance. According to Deloitte’s 2004 report on the subject, “executives seldom include clear expectations around internal control performance in service contracts, and also fail to establish the contractual right to perform internal control audits or request an SAS 70 or equivalent report.”

In addition, SOX promises to put facility and real estate departments’ financial management processes to the test. Bill-paying processes must be fine-tuned and audit-proof, and facility executives must be prepared to substantiate all capital expenses and spending forecasts, as budget-to-actual variances will be scrutinized more closely than ever.

“Facility departments probably need to be emphasizing training and internal communications, within the department and with other departments, right now,” says Boston Properties’ Silverstein. “It’s important to make sure that everyone understands their role.”

Facilities in the spotlight

SOX also brings an important change in the facility executive’s accountability and role within an organization. SOX demands a careful, ongoing accounting of all assets, including facilities and real estate, and of financial transactions that include leases, mortgages, and the purchase or sale of property and equipment. As a result, the facility executive becomes a critical link in a compliance chain that extends throughout the organization.

The extent to which this new role manifests itself varies: The smaller the organization, the greater the likelihood that it will fall to the facility department not only to implement compliance measures, but also to identify the areas where controls need to be strengthened, develop systems and processes to ensure their effectiveness, and find a way to integrate them with the organization’s overall effort. The impacts also vary with the type of organization; demands in highly regulated industries — like banking and health care — are likely to be greater. And the learning curve is steeper in some industries than in others — real estate investment trusts (REITs), for example.

“REITs, since they evolved from private companies, didn’t necessarily have a lot of internal controls in place,” says Boston Properties’ Flashman. “So in that regard the industry has probably been affected more than others where there was already a lot of legislation in place governing controls.”

As organizations work to implement new compliance programs, the facility executive may find that facility documentation — or lack of documentation — comes under new scrutiny. For instance, most organizations don’t maintain the “living documents” that are needed to accurately record changes to a facility’s physical structure over many years, or the financial systems necessary to translate facility improvements to changes in assets, says Alan Whitson, president, Corporate Real Estate Design and Management Institute. While this disconnect is never ideal, under SOX it could become a significant problem.

“Your books probably show all the walls that have been put up over 10 years,” Whitson says. “But what the books don’t show is every time you tear out one of those walls to replace it with a new one. So a lot of those walls that are on the books no longer exist. You can say that 25 percent of a corporation’s value is in its facilities, but if 25 percent of that 25 percent is no longer there, you are over-reporting your assets.”

Issues like this are best addressed through open communication between the facility executive, who should maintain records of structural changes, and the accounting department and corporate management.

“Typically, corporate managers do not consider themselves to be in the real estate business,” says Whitson. “So getting their hands on the architect’s drawings to make sure they are reconciled with any changes going forward may be the furthest thing from their minds.”

Just as SOX has changed facility executives’ roles and daily activities, the legislation has affected the skill sets necessary for staff in a variety of roles within facilities and real estate departments. “You have to make documentation and data-gathering a hiring criterion for the first level of supervision,” says Elman. “You may have someone who’s a great technician, but now there’s a whole other component to the job, and you need someone who can do that, too.”

Uncertainties remain

For all that is clear about the impact of SOX on facility management, a great deal remains uncertain. Facility executives report questions that range from day-to-day operational matters to issues that may affect their corporations’ Section 404 compliance in meaningful ways.

“Accounting is not a science, it’s an art form,” says Whitson. “And most corporations’ accounting practices are not set up for real estate.”

For instance, says CoreNet Global’s Bowles, “What does it mean to value your real estate holdings as a public company? You can go get an appraisal every year on every asset, at great cost, or you can do book-value accounting. A middle ground would be to get appraisals only on properties that have changed in value. How are you supposed to handle that? No one knows for sure.”

Increasingly, facility executives are being called upon to find ways to measure and document facility issues that, in the past, have been considered impossible to measure or not worth the effort. The depreciation of building systems as a result of after-hours use by tenants is one such issue. According to Whitson, it is just one of many gray areas that leave corporations’ facilities and real estate operations vulnerable under 404.

Technically, the wear and tear sustained by a facility’s systems as a result of tenants’ after-hours activity amounts to asset depreciation, which should be quantified, documented and reflected in the organization’s financial reporting. Practically, however, the effort involved in capturing that information hardly seems worth it.

“Landlords in general have not been fully charging tenants for after-hours use of building systems because they don’t have tools to do it,” says Whitson. “Should they be doing so, technically? Yes. You need that information to answer what boils down to an accounting question: What is the useful life of this chiller, and how much of that life is consumed by after-hours use?”

Facility executives will also continue to be challenged to interpret SOX’s relatively vague guidelines such issues as environmental issues and hazardous waste disposal.

“The law requires a level of disclosure, monitoring and assessment on those issues,” says CoreNet Global’s Bowles. “There are standards for how things should be estimated and reported, but again, they are loose.”

Examples like these illustrate one of the chief frustrations facility executives report encountering in their efforts to comply with SOX, and Section 404 in particular: The law does not make clear the level of precision that is expected, or when the effort and money devoted to compliance are enough.

“All these issues seem like small things, but the result is essentially a whole lot of rounding errors,” says Whitson. “What that means is that if someone is looking for a way to bust you, they can find one.”

SOX’s silver lining?

Along with the hassles, preparations for SOX have brought benefits to their organizations. Implementing a compliance program can bring problems to light and identify processes that need improvement.

“It’s a reinvigoration and a chance to refocus on detail processes that already existed,” says Brad Molotsky, senior vice president and general counsel with Brandywine Realty Trust. “You’re asking questions like, ‘How do my operations interact with accounting so that they can get information in a timely manner and can report accurately?’ And you’re ensuring a good flow of information back and forth to make sure that what gets filed is accurate.”

“There are lots of processes and procedures that can be improved in almost any department or company, and this process will undoubtedly help you find them,” agrees Elman. “The question is whether the issues you find are really worth all the effort.”

Critics of the legislation argue not only that the benefits of SOX are not worth all the effort and expense involved, but also that the legislation is not discriminating enough.

“Sarbanes-Oxley is a throw-the-baby-out-with-the-bathwater response to a handful of bad actors,” says Whitson. “In an effort to red flag potential problems, it has put the brakes on some legitimate business practices.”

SOX has brought increased scrutiny to structured leases and off-balance-sheet financing in general, making lenders and lessors alike wary of otherwise attractive financing arrangements. What’s more, the lingering threat of receiving a negative auditor’s statement, indicating the presence of one or more “material weaknesses” in the system of internal controls, has made many corporations justifiably jittery.

For example, when the Securities and Exchange Commission recently issued new guidance on lease accounting practices, concerns arose among large restaurant and retail corporations — among them Target Corp., Starbucks Corp. and McDonald’s Corp. — that long-standing practices would raise questions.

“They had been doing it one way for decades and then things changed,” says Sue Hensley, senior vice president of marketing, communications and media relations, National Restaurant Association. “The concern among some of our largest publicly held members was that under Section 404 it would look like a material weakness.”

The issue has since been resolved and the corporations’ fears allayed. The Securities and Exchange Commission has requested feedback from all corporations affected by SOX, with the goal of continuing to fine-tune the regulations issued under the law. Ultimately, that may eliminate some of the guesswork that complicates compliance with SOX requirements. But, in a regulatory environment of increased corporate accountability, chances are SOX is here to stay.

Keeping Contractors SOX-Compliant

As the gatekeepers for many contracting relationships, facility executives can help their organizations address the issue proactively by developing a clear protocol for managing contractors that includes:

- A comprehensive inventory of all service contracts and contractors.

- Detailed files on every existing contract, including licensing certificates and documentation of the bidding process.

- The inclusion of language in all service contracts that establishes the right to perform an internal control audit or request an SAS 70.

- Coordination with auditors and other departments to ensure that standard policies are being followed.

- A process for monitoring the level of service provided by any contractor.

“Any time we deal with a new vendor we go through an exhaustive checklist,” says Scott Watkowski, vice president of property management, Valley National Bank. “There is no question that this has made all of our agreements much more complicated, but it’s what you have to do these days.”

|

Law and Order: Patriot Act and Executive Order 13224

As if Sarbanes-Oxley didn’t give facility executives enough to think about, two other legislative measures arrived on the scene at about the same time to make things even more complicated. Both introduced shortly following Sept. 11, 2001, the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT) Act and Executive Order 13224 are designed to ferret out terrorists by blocking their ability to conduct business in the United States. Both measures effectively lower the boom on any organization that, knowingly or not, lends support to terrorists in any way, including by leasing to them, hiring them or partnering with them in a contractual agreement. Both measures carry stiff penalties and, in the case of the Patriot Act, for some organizations that are not involved in anything illegal but that fail to implement compliance programs. The message to facility executives is clear: Know your tenants and contractors.

Perhaps the best-known of the post-9/11 policy changes, the Patriot Act requires, among other things, that anti-money-laundering programs be implemented by 27 types of organizations designated as “financial institutions.” The financial institutions include loan and finance companies, investment companies and “persons involved in real estate closings and settlements.” Unfortunately, the statute does not define these terms. The Treasury Department has been working on regulations to clarify what companies are covered and how they must establish their anti-money-laundering programs, but the regulations have not yet been issued.

“The real estate industry is seen by both U.S. and foreign law enforcement agencies as a prime target for both terrorists and traditional money launderers,” says Chris Myers, partner, Holland & Knight. “It is particularly attractive to terrorists because it is both a good investment and it can provide a base of operations or safe house. So anyone in this kind of business needs to know and understand the requirements.”

Toeing the line

To ensure compliance, says Kurt Padavano, chief operating officer, Advance Realty Group and vice chairman of BOMA International, facility executives should start by adding anti-terrorism compliance clauses to all leases, amendments, loan documents and contracts, and by requiring that other parties represent and warranty their own compliance. The passage of the Patriot Act has also led organizations to emphasize physical security and to develop protocols governing who has access to what areas of a building and when.

“Some areas have to be off-limits to the cleaning crews when no one is there to supervise them,” says Scott Watkowski, vice president of property management, Valley National Bank. “They have to come during the day to clean those areas and try not to bother people, which is a good trick when you’re vacuuming.”

Executive Order 13224 designated 27 individuals and organizations as global terrorists and prohibited all U.S. citizens and companies from entering into any kind of financial transaction with them. This list of global terrorists came under the enforcement jurisdiction of the Office of Foreign Access and Controls’ (OFAC) and was combined with the existing list of Specially Designated Nationals (SDN), which includes not only terrorists, but also narcotics traffickers and money launderers. The result is a continually evolving, several-hundred-page list of the names and aliases of individuals and entities prohibited from taking part in any financial transactions — including loans, leases, mortgages and real estate deals of all kinds — with U.S. citizens or companies. Compliance demands comprehensive screening every time a financial or real estate deal is transacted, every time a new vendor is hired and every time a vendor hires a new employee who will be working on site.

“Technically, someone has to run a background check on the guy who plows the snow, even though he never sets foot in the building,” says Watkowski. “I could use a full-time investigator here.”

Responsibility for compliance is being pushed down the chain. “Owners are being required by lenders to have OFAC screening processes, and now owners are requiring it of property managers,” says Myers.

As with SOX, uncertainty comes with the territory. “Do we have to keep actual copies of every janitor’s background check on hand in the office?” asks Watkowski. “I really don’t know, but you can bet that until I find out we’re going to play it safe by keeping records on contractor companies and insisting that they are responsible for who they hire.”

|

Abigail Gray, a contributing editor to Building Operating Management

, is a writer who specializes in facility issues. She is the former editor of EducationFM

magazine.

Related Topics: