How Facility Managers Can Best Manage Stress

If you're not managing stress, it's managing you. Here are some tips for staying sanguine.

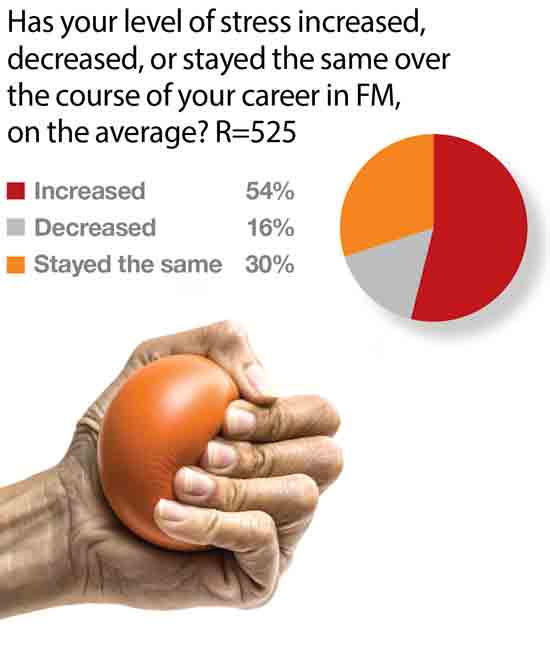

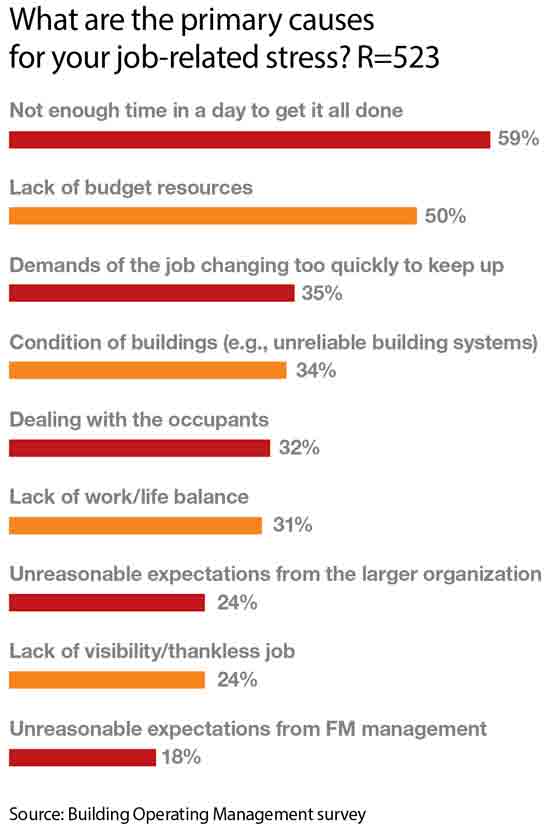

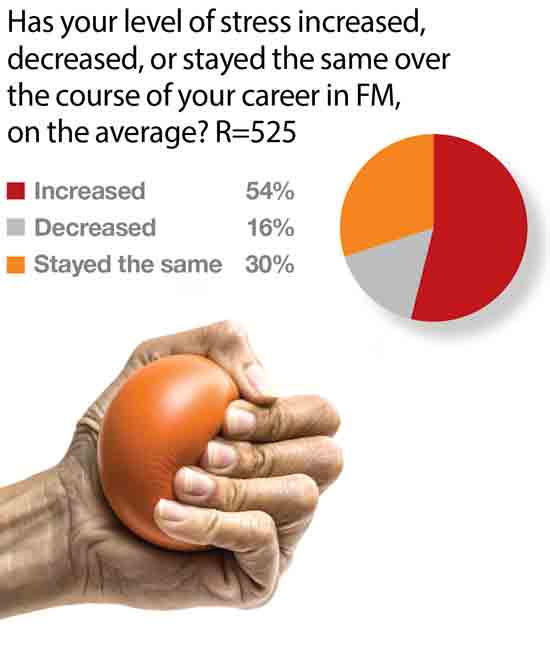

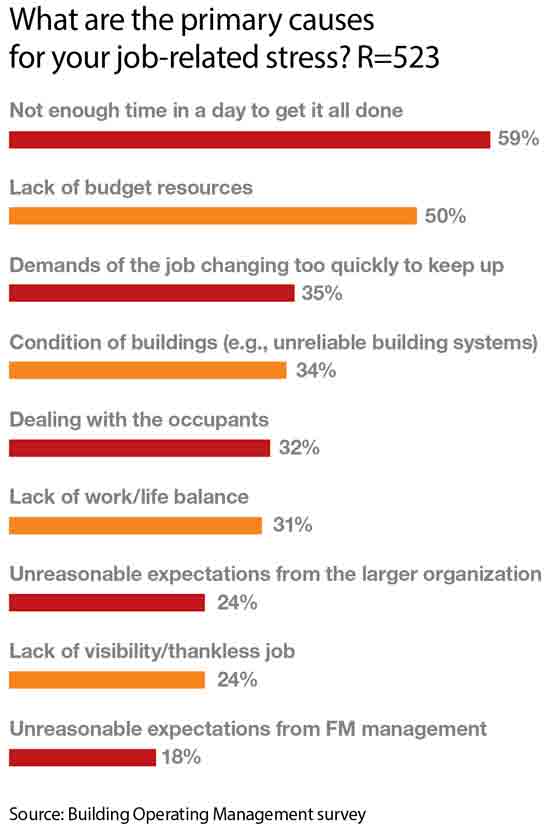

Three out of four Americans are stressed out, with one of them facing high levels of stress, according to research from Harvard Medical School. To facility managers, that’s hardly news. Respondents to a recent Building Operating Management survey on stress among facility managers reported that 71 percent feel they are moderately stressed on a day-to-day basis because of their job, and an additional 14 percent are very stressed.

Facility management, with varied and sometimes unpredictable daily challenges, often shrinking resources, and ever increasing demands, can be a stressful job. However, these challenges are not necessarily unwelcome. Many a facility manager has described himself or herself as an “adrenaline junkie” and touted the benefits of having no two days alike.

When asked whether there was a time when job-related stress directly impacted their performance, either in a good or bad way, many respondents to the Building Operating Management survey said they liked the stress of the job. “I like a challenge,” said one. “When others say it can’t be done I like to prove them wrong.” Another responded, “It’s part of the job ‘fun.’” Many others simply expressed that stress is just “part of the job.”

Given the fact that the demands of the job are never going to get less complicated, it is important for facility managers to be aware of their stress levels, and develop ways to cope with, and even harness, their job-related stress, both for their own benefit and for the sake of the teams they lead.

The many sides of stress

In our modern lives, “I’m so stressed out,” has become almost a throwaway phrase. But just because we’re nearly all in the club doesn’t mean it should be accepted as a normal and healthy way to live out our lives. The tricky thing about stress is that there are many sides to it. The quality, duration, impact, and perception of stress are almost as unique and varied as the people experiencing it. Here are some parameters to keep in mind when thinking about stress.

• Quality of stress. Our bodies have developed mechanisms to respond to acute stress, the kind that needs immediate action. Sweaty palms, the better to grip and throw with. Racing heart, the better to sprint away. “That stress response is great for dealing with lions, tigers, and bears,” says Scott Crabtree, CEO at Happy Brain Science, a consulting firm on productivity, happiness, and creativity. “And not so great for dealing with stress sustained over time.”

That fight or flight mode is a continuum, says Crabtree. It’s not just a switch that snaps conveniently on and off. When chronically stressed, people’s brains start seeing only three solutions to problems: fight, run, or freeze. Freezing is actually the default response to intense stress, says Crabtree. Again, “great for lions and bears, not so great for handling tenant emergencies or complaints.”

• Perception of stress. As noted earlier, facility managers sometimes say they like the stress of the job. “Stress is good if you know how to manage it,” says Bill Paquet, regional facilities manager for Allina Health, in one of his responses to the Building Operating Management stress survey. “It makes you focus like a laser.”

This kind of stress is “eustress,” defined as moderate or normal psychological stress that is interpreted as being beneficial, says Crabtree. A positive perception of stress provides a level of protection against the negative health effects of stress. “Research coming out of Harvard says that if you view stress as a helpful, energizing force, you feel better psychologically, and it doesn’t take as much of a toll on your body,” says Crabtree. In particular, blood vessels do not constrict as much. Of course, a negative perception of stress augments its harmful effects on the body. But in either case, chronic stress will have a negative impact, no matter the perception of it. “If you’re just sort of always stressed out, that starts to take a toll on your body,” says Crabtree. “Less of a toll if you think, ‘This is great. I’m energized.’ More of a toll if you think, ‘This is horrible. I’m really stressed out.’ But both, if long-term prolonged stress, are not healthy for your brain and body.”

• Physiology of stress. Part of the reason different people react to stress in different manners has to do with brain chemistry, specifically dopamine. There are two camps of people, those who clear dopamine from their brain quickly and those who don’t, says Crabtree. Fast dopamine clearers need excitement to do their best work. “The stress of a deadline injects their brain with dopamine, so to speak, and they clear it quickly, leaving them in a productive, focused zone,” he says. Slow dopamine clearers are left unable to focus when faced with too many deadlines or demands. They get stuck in panic mode.

There is also a sweet spot on the stress continuum. People tend to think that the optimal place to be is somewhere with very low stress, preferably sipping something with a little umbrella on the beach. However, “what science has found is that the happiest moments of our life are pretty intense challenges — when we have the capabilities to meet the challenge,” says Crabtree. “If a facility manager is dealing with a very complex situation, and it’s right at the edge of his or her ability, and she or he gets completely absorbed in the work where everything is clicking and a sense of time starts to disappear, that is a zone called ‘flow.’” High engagement and a feeling of being in control are hallmarks of flow.

Related Topics: