The 1970's Energy Crisis Shined a Spotlight on Facility Management

Buildings in the '70s were not energy efficient. Facility managers showed the country how to reduce energy use and save money

By Dan Weltin, Editor-in-Chief

“Building Operating Management’s” roots date back to the 1950s. However, until 1970, the publication was known by other names: “Better Maintenance,” “Better Building Maintenance,” and “Building Maintenance and Modernization.” To celebrate the magazine’s 70th anniversary, every month, FacilitiesNet is looking back at each of the seven decades since its inception.

The 1970s start with a focus on the environment, and it would never stop. With Earth Day launching and anti-litter campaigns hitting the airwaves in 1970, it’s no surprise that the biggest issue facing facility managers that year is waste disposal.

“Americans are finally listening to the warning of scientists and ecologists that our finite atmosphere may soon be polluted beyond repair, our natural resources may be used up, and our mountains of solid waste — products of the ‘good life’ — may bury us,” according to a 1970 article.

U.S. yearly waste weighs 3.5 billion tons in 1970. Recycling of paper and metals and composting start to be seen as alternatives to older waste management solutions of incinerators and dumping.

In addition to waste, air pollution is rampant. In New York City, sulfur dioxide levels reached .23 parts per million parts of air in some places, compared to the federal emissions standard of .1 ppm. New air control legislation is passed in major cities to reduce pollution and smog.

In just a few years, however, these environmental issues, while important, would take a backseat to another crisis. In 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries instituted an embargo that limited the amount of oil sold to the United States, doubling fuel prices.

By the time of the 1973-74 energy crisis, commercial buildings consumed an estimated 3 percent of the nation’s energy. Building owners and managers faced pressure to conserve energy. Whether it was reducing petroleum products to heat the building, citizens complaining about using energy to light the building at night, or occupants insisting on reducing corridor and office lighting, facility managers and the entire industry had to change.

“The energy crisis has become a dramatic reality to the American public. We in the real estate industry have always been aware of the need to conserve energy. Now, more than ever, we must emphasize that need and act upon it,” wrote Robert Campbell, director of management, Kenneth D Laub & Co., Inc., in 1974.

Buildings at that time were not designed for energy efficiency. Half the energy utilized for heating and cooling was wasted through heat loss of building materials. Facilities typically had between 50 and 100 percent glass perimeter walls. However, glass walls are poor insulators, resulting in substantial heat loss in winter and solar heat gains in summer. Many newly constructed facilities favored fewer windows. For those windows that did remain, the invention of low-emissivity window coatings or "low-e" helped reduce energy by as much as 40 percent.

In addition, prior to the energy crisis, office spaces, corridors and even restrooms were encouraged to be brightly lit without a care for energy usage.

“The basic energy problem is with the buildings themselves. Virtually every existing building was designed to waste energy. Not consciously, perhaps, but these buildings were designed when energy was cheap. The objective then was comfortable interiors. And that meant prodigious quantities of fuel and power and light.” says Preston Bond, regional service manager with Honeywell’s Commercial Division in a 1974 article.

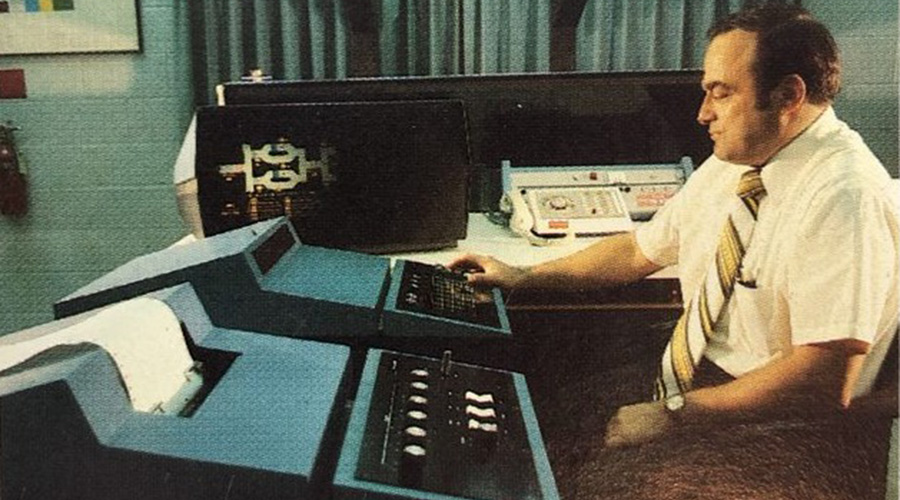

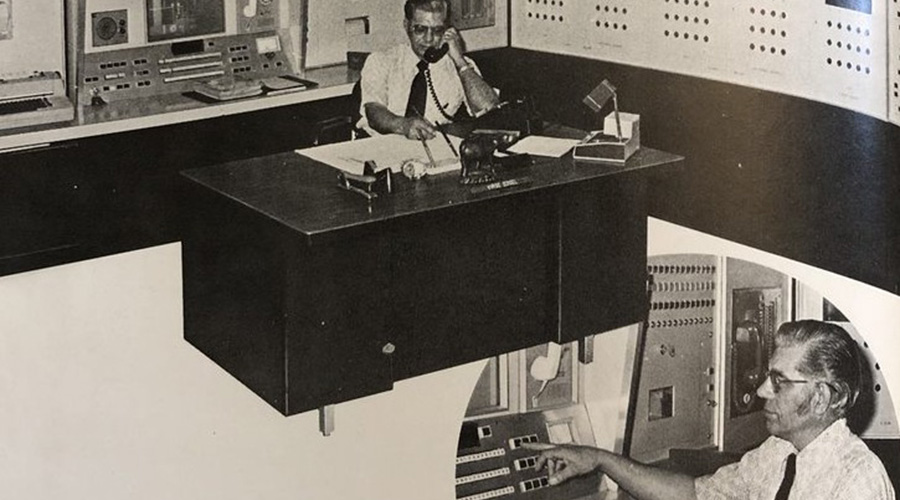

The shortage of fossil fuels and escalating prices for building owners justified the investment of computerized control systems and building automation. As technology improves over the next several years, more buildings use automated energy management systems for total building control. Computers program the most effective use of HVAC, lights and elevators to save energy. In addition to energy management, computerized systems take control of life safety, security, and other equipment monitoring.

“The computerized automation system is a most important management tool in the fight against excessive use of energy,” wrote Louis F. McTague, vice president of management operations for Cushman & Wakefield in a 1975 article.

According to U.S. Federal Power Commission in early 1974, approximately 25 percent of the available energy was used to generate electricity. Of this, 5 to 6 percent was consumed for lighting. As a result, along with the use of computerized controls, lighting manufacturers released new products designed to use 10 to 20 percent less energy.

By 1976, half of the country’s energy consumption was from foreign sources. There was a tremendous effort to lessen the country’s dependence on foreign energy sources and in 1978, President Jimmy Carter introduced the National Energy Act, which established goals to increase the use of renewable resources.

Originally, many in the industry thought that alternative energy meant nuclear, but soon started experimenting more effectively with solar power.

“The dream of low cost, nuclear generated electricity remains just that,” wrote Peter Flack of Flack & Kurtz in a 1976 article.

With pressure from Federal and state agencies to expand building codes to include energy performance standards, in 1975, ASHRAE developed “Energy Conservation in New Building Design” as part of Standard 90-75 (the standard for existing buildings was started around the same time, but wouldn’t be ready until the 1980s). Several states use this standard as a model for their own standards. A few years later, the newly created Department of Energy drafted its Building Energy Performance Standards in 1979.

At the end of the decade, another oil crisis once again put a renewed focus on conserving energy. In July 1979, President Carter issued his Emergency Building Temperature Restrictions Plan. Thermostats must be set no lower than 78 degrees Fahrenheit in summer and no higher than 65 degrees Fahrenheit in winter. Tenants that disregard the order could be fined up to $10,000 per day.

Irresponsible energy usage wasn’t the only way facility managers could receive fines during the decade. In 1971 the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) is enacted. The act is designed to “assure so far as possible every working man and woman in the nation safe and healthful working conditions.”

The original law wasn’t always clear and sometimes omitted specific building types, but facility managers, along with the rest of the country, soon learned that an OSHA inspector can issue a citation for any condition deemed unsafe no matter the area or industry. Also, any employee can file a complaint that will trigger an inspection.

By 1973, OSHA issued 3,032 citations alleging 16,738 violations of job safety and health standards. Penalties totaled $425,738.

“By this time, most people who have had any contact with the OSHA law, have noticed that this little law has created a lot of confusion,” wrote Brian Kilkelly, Lithonia Lighting in a May 1973 article.

One way OSHA directly affected facility managers early on was requiring specific colors for safety and color mark physical hazards and safety, firefighting and protective equipment. For example, all fire protection equipment, including fire alarms, sprinklers and exit signs were to be painted red. Falling or tripping hazards were designated yellow.

Dan Weltin is the editor-in-chief of the facilities market. He has more than 20 years experience writing about facility-related issues.

Related Topics: