What You Need To Know About Energy Benchmarking and Disclosure Ordinances

First part of the 5-part Green Building Report.

The spread of energy benchmarking and disclosure ordinances across the U.S. has been one of the more interesting developments around sustainability and existing buildings. But the ordinances themselves aren’t the whole story. Along with those regulations is a growing array of programs and tools that can help facility managers make the most of benchmarking by improving the energy efficiency of their buildings.

Benchmarking ordinances are a rare form of government policy that touches existing buildings. More usually, code criteria that are triggered by permit-requiring renovation projects have been the means by which governments can require improvements in existing building energy efficiency. Benchmarking and disclosure ordinances are a new tool, with the specific goal of bringing energy performance information to light in the hopes that market forces can then drive efficiency gains. Broader goals include reducing greenhouse gas emissions from buildings, improving the health and productivity of the people within buildings, and creating economic opportunity and resiliency.

The Institute for Market Transformation (IMT) and Pacific Coast Collaborative (PCC) explain that the goals of benchmarking and transparency policy are to drive “behavioral and operational changes that bring immediate and low-cost reductions in energy consumption” and empower “consumers to more easily understand how buildings are performing and reward owners of efficient buildings.”

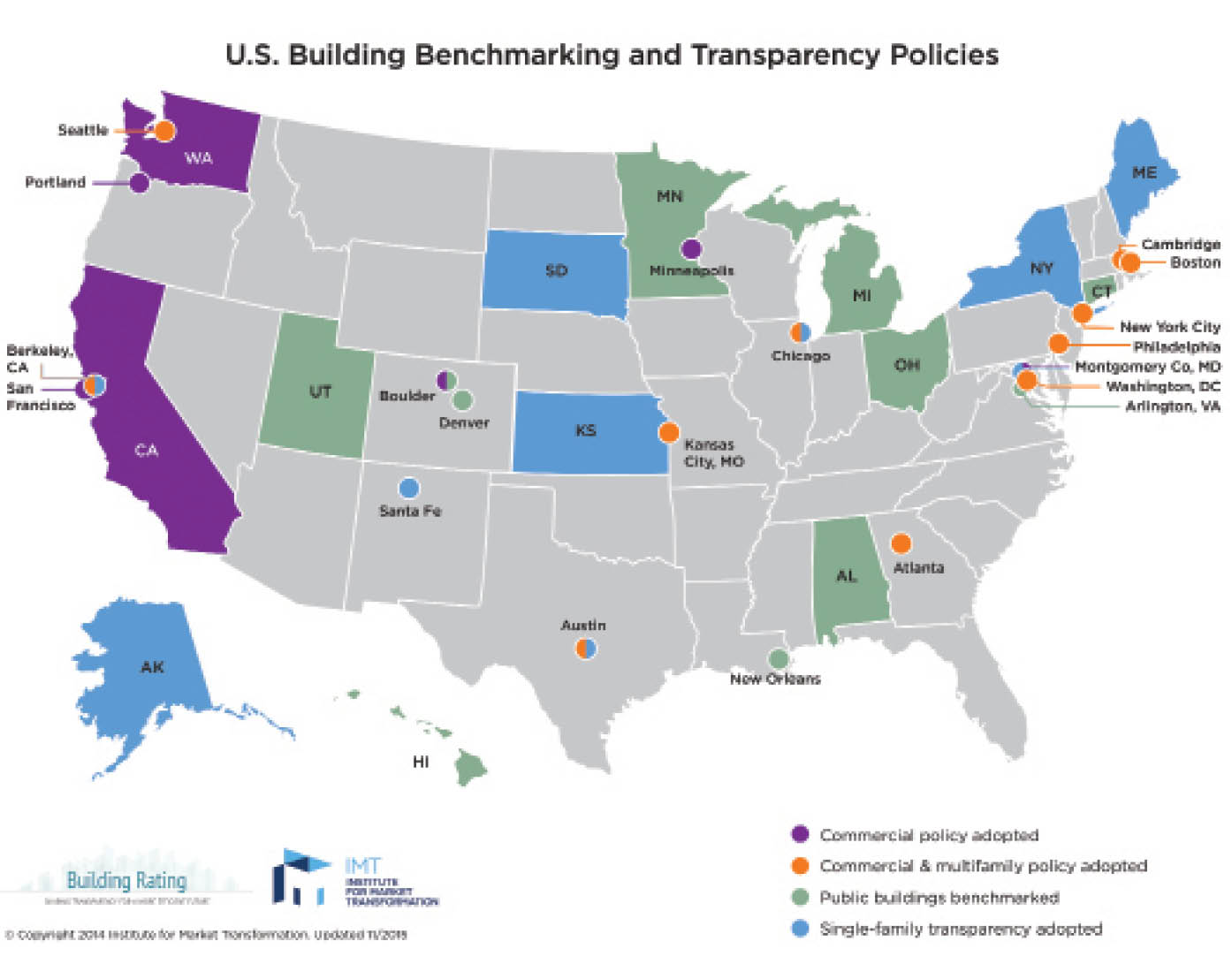

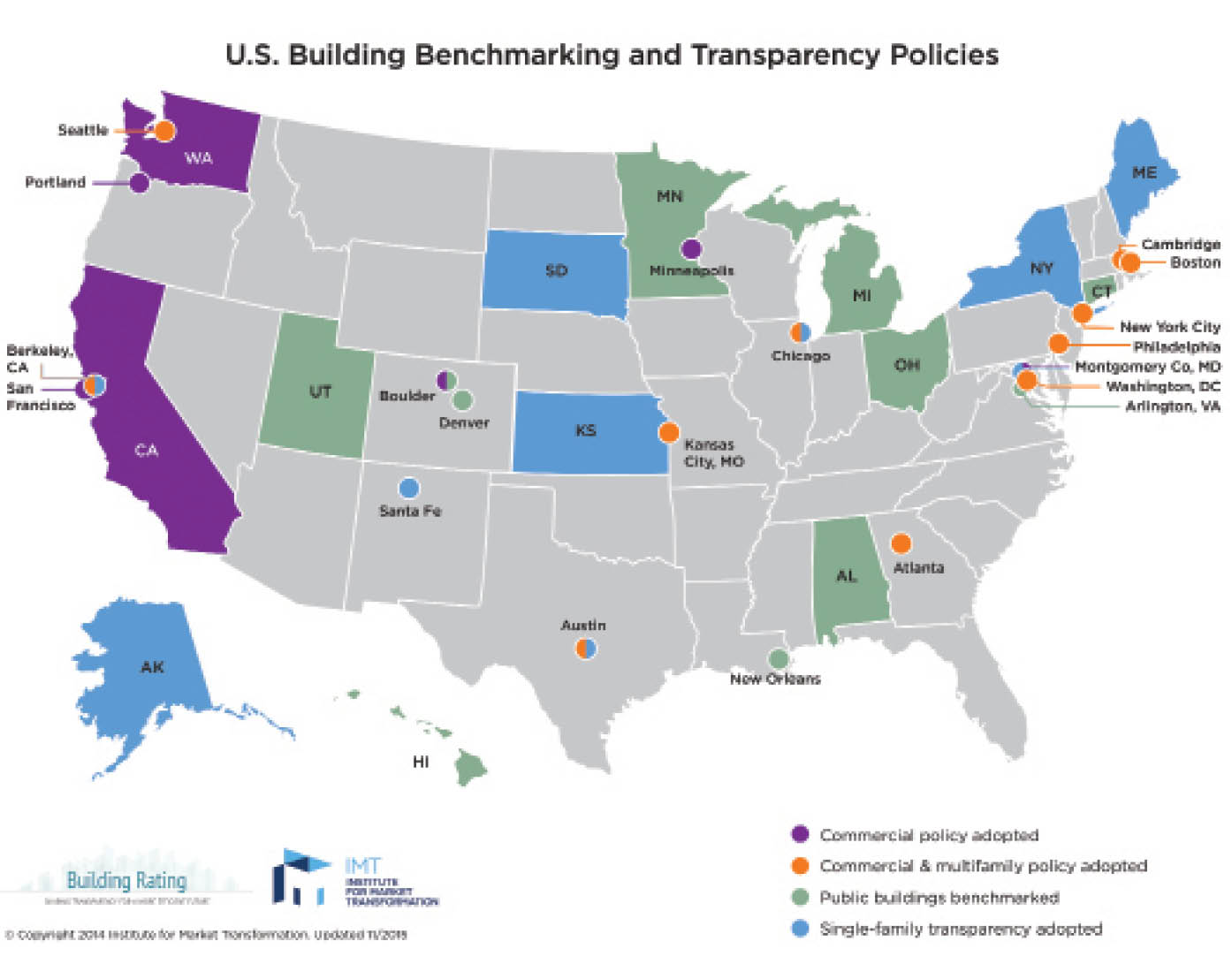

Not surprisingly, California led the charge, passing a statewide benchmarking ordinance back in 2007. More commonly since, it is cities passing ordinances, with model language helping along their spread. At present, the tally in the U.S. is 15 cities, one county, and two states. (See “U.S. Building Benchmarking and Transparency Policies” below.)

Many expect these ordinances to continue to spread, despite what is sometimes organized opposition from building owners.

There are several key forces that make expansion likely:

• Buildings are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, garnering their own day at the 2015 COP21 climate talks in Paris.

• As cities form climate action plans, they will look for options to influence energy consumption in buildings. Cities are increasingly crystallizing as the right scale for strategic action around climate issues, and they cannot get far without promoting efficiency actions in privately owned buildings.

• At a base level, these ordinances rely on market-based solutions to climate change, which is a common first-wave strategy for environmental regulation. Whether or not they evolve in stringency may depend on how much progress is realized through the voluntary market-based tactics.

How to Begin Benchmarking

Energy Star Portfolio Manager has become the de facto (and free) benchmarking tool. As novice users engage in benchmarking, it is important to understand common trouble spots and how to get around them.

“For many building operators, setting up an Energy Star Portfolio Manager account and building profile is a new tool to work with and manage,” says Katie Kaluzny, associate director of the Illinois chapter of USGBC. “There are many live and on-demand webinars and short videos on Energy Star’s website for first-time users. Also, many cities, like Chicago’s Energy Benchmarking Working Group, are providing free in-person trainings, call centers, and drop-in office hours to familiarize new users with the tool and building inputs.”

But even gathering the utility data for a given building can require a surprising amount of legwork, and there are plenty of causes for trouble: estimated readings from the utility, meters serving unknown areas of the building, separately metered tenant spaces with tenants queasy about sharing their data, calibration problems, and so on.

Say you are a property manager who adeptly complied with a new benchmarking ordinance, only to find that your building is among the worst performers. Furthermore, your building’s performance is now public information, and given market conditions, the leasability and asset valuation of the property may be affected. You are ready to take action on performance improvements, and want to be able to tell a positive story. What do you do?

Though benchmarking and disclosure ordinances are very much intended to bring about this confluence of information and pressures towards action, organized support and resources to aid newcomers into energy efficiency best practices are not always well-coordinated or promoted. In some cases, this is almost by design, as the ordinances are mostly positioned to unleash market forces by bringing energy performance information to light, and there is lag time between a new market opportunity and a well-developed and vetted ecosystem of product and service providers who can help. Another reason is that local governments are not flush with cash, and therefore do not necessarily have the financial and human resources to establish programs to engage the lower-performing buildings in prescriptive or tailored improvement strategies.

A number of municipalities go beyond just benchmarking and disclosure in their ordinances, actually stipulating energy efficiency actions that must be taken as well. These required actions give a hint to any building owner or manager about where the best starting points lie in crafting an effective efficiency improvement strategy: Energy audits and retrocommissioning are the go-to procedures for developing a tailored efficiency strategy in a given building. In New York City, for example, a series of four local laws, which make up the City’s Greener, Greater Buildings Plan, were passed to bring about energy efficiency improvements in existing buildings.

Related Topics: