Demand Response 101: How To Get Paid To Cut Power Use

Why would a utility pay you to use less of the only thing they sell? Here's why.

Programs that pay power customers to reduce their electric loads are expanding and becoming more sophisticated. Called demand response (DR), this option is becoming available as more so-called smart meters (needed for the process) replace mechanical meters. Unlike demand-side management programs that pay customers to permanently reduce power consumption (i.e., kilowatt-hours) through energy efficiency projects, DR programs pay them to temporarily reduce the speed (i.e., kW demand) at which they are using power. Many facility managers are cashing in on opportunities to adjust their hourly electric loads while maintaining full building services.

Demand response 101

DR programs have been available in some areas for over a decade. But several advancing technologies and issues are making DR programs more feasible and economically desirable, bringing options to customers that previously found DR too challenging or unprofitable to consider.

But why would a utility, whose business is selling power, pay a customer to use less of it?

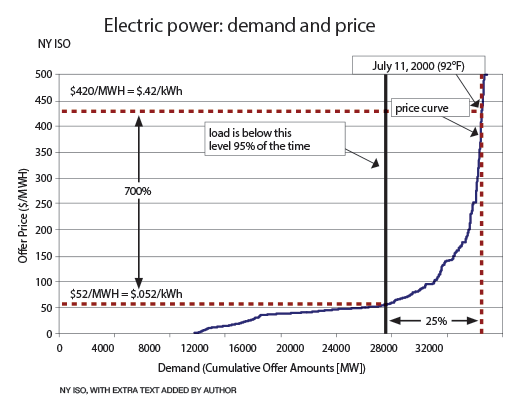

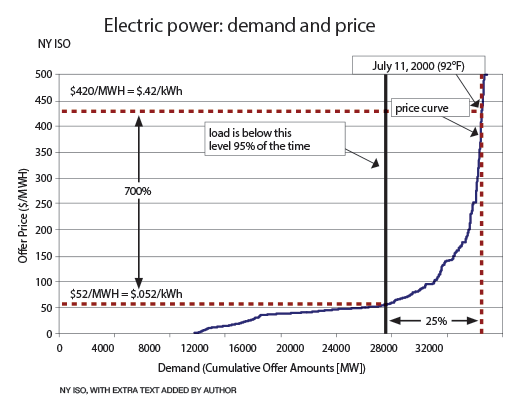

Most utilities buy a portion (in some cases, most) of the power they sell from wholesale grids that manage power made by private non-utility generators. Those grids are called power pools, independent system operators (ISO), or regional transmission operators. Every hour, wholesale power suppliers offer their electricity to grids through a competitive bidding process. The grid operators buy as much as needed to meet the next hour’s projected grid load. When that load is low, a supplier drops its price to increase the chance that its power will be bought. But when grid load rises, and the margin between hourly load and generating capacity tightens, suppliers are able to greatly raise their bids, pricing may rise exponentially. As shown in the chart below (“Electric power: demand and price”), a 25 percent rise in hourly grid demand yielded a 700 percent increase in hourly price. Even where power prices are fully regulated, price spikes may be passed to customers via fuel (or energy) adjustment charges.

(As power suppliers charge what the market will bear, pricing may rise exponentially. In the case shown above, a 25 percent rise in hourly grid demand yielded a 700 percent increase in hourly price.)

While some regulatory limits exist on such volatile pricing, they are designed to allow market price “signals” that attract new generation or transmission to compete with existing supply, eventually forcing pricing back down.

Even utilities that generate most of their electricity often need to buy power when hourly load exceeds their plants’ capacity. To avoid paying very high prices for purchased power, they may instead pay customers to cut back on their demand or (where allowed) briefly run on-site emergency or backup generators to reduce their metered load. When hourly prices spike, even a small drop in grid load may yield a big drop in hourly price, and save more than the demand response incentives the utility pays to customers. The result is a lower hourly cost for all customers.

Under typical weather and economic conditions, calls to reduce demand may total only a few dozen hours a year. Extended hot weather, however, may result in more DR calls, with greater durations. A recession may push prices down, reducing the likelihood for calls.

Related Topics: