7 Ways To Finance Energy Efficiency Projects

Use these financing mechanisms to help defray first and long-term costs of energy conservation measure projects.

There are many ways to fund energy-conserving projects, and more than one should be considered. Utility costs typically don’t decrease over time, so keeping energy use down over the long term is critical to maintaining cost savings. As mentioned above, BEMIS can help lower those costs — often automatically. Beyond reducing costs, there are many other ways to fund energy conservation projects. Following are seven of the more common.

1. PACE (property assessed clean energy): Started in 2008, PACE funding is now available by statute in more than 30 states and the District of Columbia. It provides funding by tax assessment for deep energy retrofits and energy-conserving measures in new buildings — with no up-front layout of money by an owner. To date, PACE has provided more than $400 million for energy-improving projects in commercial buildings — and it just has a toe-hold in most states in which it is available.

2. PPA (power purchase agreement): With a PPA or similar program, equipment or systems that contribute to energy use are paid for and maintained by a vendor for extended time periods. This includes not only the systems typically replaced, like HVAC and lighting, but also windows and building envelope. It also requires no up-front layout of money by an owner.

3. Energy performance contract (EPC): EPC is a turnkey service, sometimes compared to design/build construction contracting, typically delivered by an energy service company (ESCO). It can provide customers with a comprehensive set of energy efficiency, renewable energy, and distributed generation measures. Often it is accompanied by guarantees that the savings produced by the energy-conserving project will be sufficient to finance the full cost of the project.

4. Utility rebates: Many gas and electric utilities offer rebates for energy-conserving retrofits to existing buildings, as well as installation of energy-conserving equipment on new buildings. Often the contractors that install lighting, HVAC, roofing, windows, etc. will perform the paperwork for the owner. To see if your state has any rebates, visit www.dsireusa.org, the Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency.

5. Tax credits/deductions: Some of the better-known tax credits and deductions are for solar and geothermal systems. Not as well-known are 179D and cost segregation deductions. Many of them have sunset dates so it is necessary to do some sleuthing before getting too excited.

6. 179D commercial buildings energy efficiency tax deduction: This one started in 2006, was extended several times, and expired Dec. 31, 2016. It can be used for installing qualifying systems in construction projects placed in service by the end of 2016. The complex qualifications have changed over the years, but it generally provides for a tax deduction of up to $1.80/square foot. There currently are bills in Congress, with new modifications, to extend it again, but none have yet passed.

7. Cost segregation: Cost segregation is the practice of identifying assets and their costs, and classifying those assets for federal tax purposes. In a cost segregation study, certain commercial building costs previously classified with a 39-year depreciable life, can instead be classified as personal property or land improvements, with a 5-, 7-, or 15-year rate of depreciation using accelerated methods. An “engineering-based” study allows a building owner to depreciate a new or existing structure in the shortest amount of time permissible under current tax laws.

To stay in the game, and stay profitable for the long term, you must be flexible. Keep up with new technology, certifications and energy and cost–saving measures.

James Newman (jimn@newmanconsultinggroup.us), CEM, CSDP, LEED AP BD+C, is owner/managing partner of Newman Consulting Group.

Email comments and questions to edward.sullivan@tradepress.com.

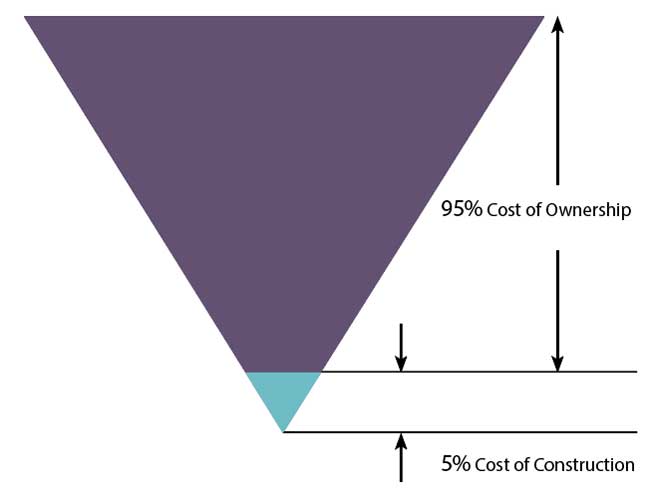

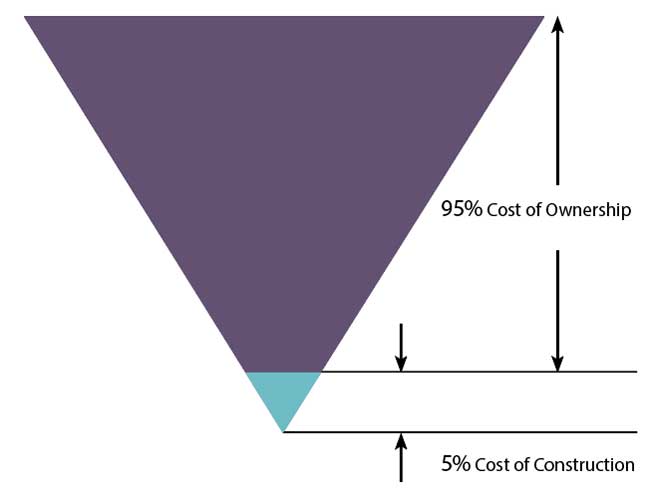

TOTAL COST OF OWNERSHIP

Keep in mind, first costs pale in comparison to long-term costs in a building, so using technology to save energy has a much bigger impact on the bottom line over the life of a building.

Source: U.S. Federal Facilities Council Technical Report No. 142

Related Topics: