High-Performance Buildings: Managers Influence Design, Construction

Enough was enough. After three failed attempts to generate funding for its aging facilities more than a decade ago, Seattle Public Schools created a program that has become the primary vehicle for addressing deferred maintenance and implementing capital projects in the district.

The district implemented the first phase of the Building Excellence Program (BEX) in 1996, signaling a shift in the district’s approach to maintaining and revitalizing its facilities. The district is home to 94 classroom buildings, but one-third of those schools are at least 50 years old. As buildings aged, maintenance issues multiplied. The district focused its attention on getting the public on board with its plan to renovate or rebuild facilities to ensure they met modern educational and building standards.

“The public finally had decided that enough was enough, and they wanted their old, historic buildings fixed up in the neighborhoods,” says Don Gillmore, the Building Excellence construction manager. “Seattle is a city of neighborhoods, and it’s very mixed demographically, so a lot of folks wanted the old buildings repaired.”

The public has passed two capital levies and one bond comprising the three phases of the BEX program — BEX I, BEX II, BEX III. The district has completed almost all the construction associated with BEX I and BEX II, and the projects in BEX III are set to begin.

Madison Middle School is one example of the district’s commitment to constructing facilities that promote environmental responsibility and fulfill educational goals. Before the district renovated and rebuilt Madison, deferred maintenance led to mechanical and electrical issues that elevated the district’s utility costs and carbon footprint. The building also could not accommodate the technology the district wanted to incorporate to improve its educational opportunities. Madison’s before-and-after pictures show just how far Seattle Public Schools has come in building support for renovating schools and addressing deferred maintenance within those facilities.

Collaborative Effort

To build facilities that accomplish a district’s long-term goals of lowering utility costs and improving students’ educational experiences, both the maintenance and construction managers need to be involved in the design and construction process.

“We just finished a year’s worth of seminars with our capital people and maintenance people together,” Gillmore says. “We probably had a hundred people in the room every couple months to discuss maintenance issues and capital issues. We formed subcommittees that were joint committees of maintenance and capital people in order to address not only the maintenance issues, but also how the capital people can help maintenance when the building is constructed and completed.”

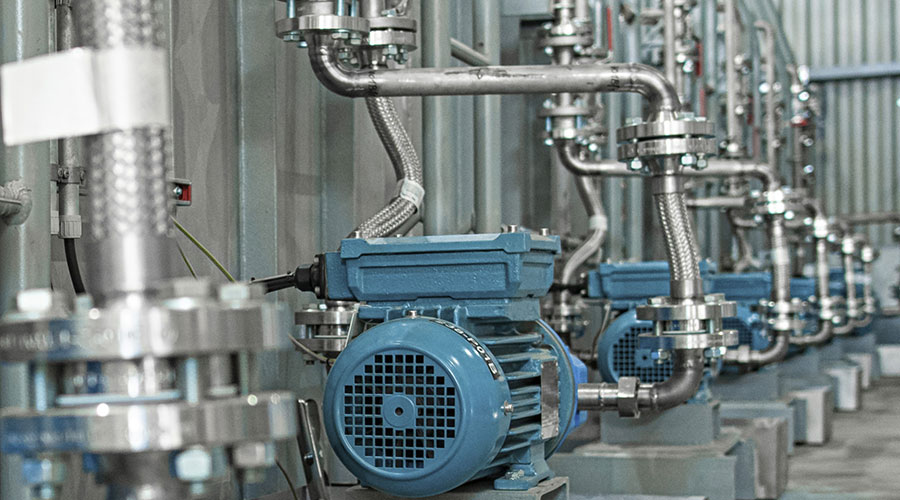

The relationship between the maintenance and construction departments was not as developed as it is now, says Fred Stephens, the district’s director of facilities. The district has done a better job understanding the way the design and construction processes can affect maintenance and operations. For example, when construction personnel are specifying HVAC controls, they work to ensure they select standardized products that will reduce the maintenance requirements during the system’s life cycle.

“We talk about the work that the maintenance organization is going to have to perform,” Stephens says. “We’re careful to make sure we have both folks in the room when we make these decisions. And there’s a third component, which is a planning component.”

As many managers know too well, excluding maintenance and operations in the early stages of the project can lead to nagging issues. Fortunately for Seattle Public Schools, the collaboration between construction and maintenance has led to high-performance facilities that operate as intended.

“As the drawings are developed, we have three reviews by the maintenance department of the actual drawings themselves,” Gillmore says of projects included in the BEX phases. “(Managers) can review what’s being proposed to be implemented into the school. We also try to construct buildings that are relatively bulletproof so the maintenance load is greatly reduced because, of course, our maintenance budget is always an issue.”

But before plans for capital improvements get underway, the district has to generate support among its citizens to approve funding. An organization called Schools First has become the campaign arm of the BEX programs. Since its inception, the voters have approved every capital levy or operating levy on the ballot, Stephens says.

“It is a disciplined, sophisticated campaign organization,” he says.

Adds Gillmore, “This was a group of civic and business leaders who realize the importance of education in Seattle and wanted to promote healthy, structurally sound buildings.”

The work performed by Schools First on the front end of the BEX programs ensures schools such as Madison Middle School receive the funding necessary to restore and revitalize their components and systems.

Related Topics: