Maui Wildfire: A First-hand Account

8/2/2024

On Aug. 8, 2023, I flew into Maui from the Big Island of Hawaii for a four-day adventure based in Lahaina. Unfortunately, on that day, Maui experienced the worst natural disaster in state history and the deadliest U.S. wildfire in over a century.

According to the Maui Police after-action report, the fires claimed 100 lives, burned 1,283 acres upcountry, 3,240 acres in south Maui, 2,170 acres in Lahaina, and over 3,000 dwellings in Lahaina.

While the impact on me is minor compared to the impact on the families and community in Lahaina, I wanted to share my story in the hope that lessons I have learned along the way will help others.

Worst natural disaster in state history

My trip was an impromptu solo vacation planned only two months before. Hawaii was on my bucket list and I picked the Big Island and Maui because I wanted to visit the national parks.

Mid-day, Tuesday, Aug. 8, I drove to Lahaina heading around the west coast of Maui. The winds were strong, close to 60 mph, and the drive was treacherous. I felt anxious and knew I needed to get to my hotel as soon as possible.

As I arrived in Lahaina around 1:30 p.m., power lines were down and the road was covered with debris and fallen coconuts. My hotel was on the north side of Lahaina and upon arrival, power was already out at the resort and there was no cell service. I suspected the power might be out for a while, so I decided to buy water and non-perishable food from the market at the resort. The resort had an emergency generator and was able to power part of the first floor and the elevator. I had lunch and powered up my phone, completely unaware of what was unfolding two miles to the south.

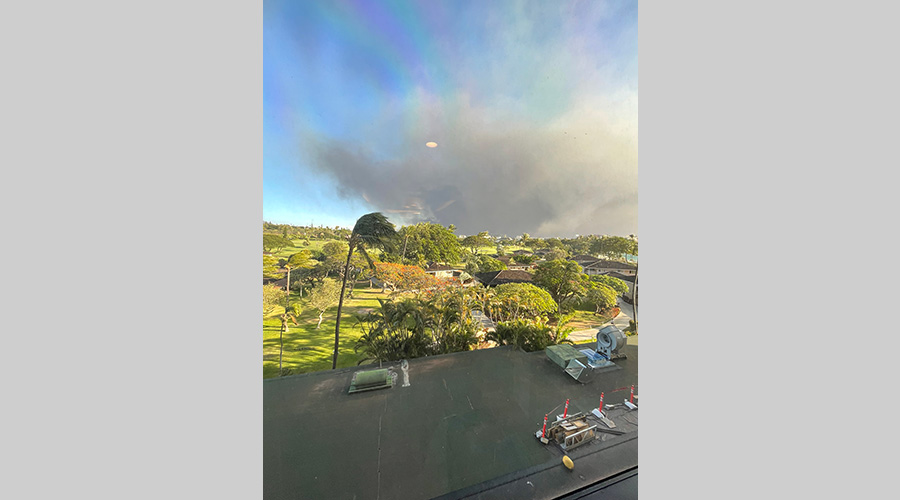

As I went to my room, I saw smoke and I knew there was a fire nearby. I thought I might be evacuated at any moment, so I packed a go-bag. Having led my company’s emergency preparedness and business continuity planning, I knew the importance of a go-bag and the need to be ready to evacuate. I put a change of clothes, food, water, and electronics in my backpack. Because I was planning on hiking in the park, I brought my Garmin GPS which has satellite phone capability and a headlamp. Both proved to be very important. Cell service was still down but I was able to send a text through the GPS to my family to say I was safe. As it got dark, I braced myself for a long night, and I heard helicopters and emergency sirens throughout the night. Little did I know, that people were jumping into the ocean to escape the fire.

In the morning, I put my cellphone out on the balcony to see if I could get any reception. I suddenly heard a ding indicating a text came in and then it kept going. I had received over 50 texts from people wanting to know if I was OK, having seen the wildfire coverage on the news. I could receive text messages, but I could not make phone calls or send texts. The texts were telling me this is the worst natural disaster in the state and that I needed to get out. Hotel employees had limited information due to the lack of cell service. The employees, many of whom did not know if their families were alive or if their houses were standing, were struggling to get information. One thing we did know was that the road to the south was closed.

At this time, it felt like the safest place to be was to remain where I was. What I did not know until I left the area and realized the full devastation, was that we were completely trapped in that hotel.

I would learn later that two key routes out of town, the Honoapi‘ilani Highway and Lahaina Bypass, were either fully or partially closed that day. One of the heartbreaking facts about the loss of life is that a large number of people died in their cars trying to get out. Witnesses stuck in traffic recalled seeing the fire in their rear window and thinking that other motorists trapped behind them were likely dying in those moments.

3 takeaways for improvement

Having experienced this tragedy first-hand, I feel as a facility management consultant I can offer some takeaways to help facility managers improve emergency response in the future.

Takeaway 1: Communications will fail during an emergency. We are told this over and over but until you experience it, you don’t understand how completely in the dark you could be. In the first three days of the event, the hotel did not communicate with guests in any organized manner. Rumors were flying around the hotel, and it was difficult to know what was happening just a few miles away. There is a sense of powerlessness when you don’t know what is happening.

When you travel, you often have limited information about the area. Hotels usually display the evacuation routes out of the building, but not the evacuation centers. If I had been evacuated out of the hotel, I would have had no idea where to go.

By Thursday morning, I knew I needed to find a way out. My friends and family on the east coast were following the news and by the time I woke up they told me the road should be open. I confirmed with the front desk, they wrote my name down on a piece of paper with my departure date, and I got in my rental car and hoped for the best.

Related Content: Facility Managers Face Year-Round Wildfire Challenges

The National Guard was at every intersection, guiding the way out. The devastation was unbelievable. As I drove slowly through the devastation, I saw the cars that were completely burned and buildings utterly incinerated, with nothing left. The National Guard was only letting people out and only emergency vehicles were able to come in.

I flew out Friday on a very large plane that had come to the island with no people and only emergency supplies. I was very grateful and thankful that I was able to safely go home. When I got home, I immersed myself in the news of the event and reflected on things I would do differently -- which leads me to my second takeaway.

Takeaway 2: We need to take emergency warnings seriously. This is a collective WE, a societal WE, and I include myself in that group.

I can’t say I did not know the risk. The meteorologists forecasted high winds for at least a week before the event. As I was on my way to Maui, I asked the woman sitting next to me on the plane, who was from Maui, if the high wind forecast was unusual and she said, that is just Maui, it is always windy. I looked at the hurricane forecast (Hurricane Dora) and it was 500 miles away from the islands and heading in a straight line, which meant all of the islands could be impacted. I made a calculated risk that this was one day with high winds as the hurricane passed. I would be careful, but thought it is likely just one bad day.

What I did not know is the area where I was staying was the dry side of the island and was in a severe drought. I did not know that Hawaii has a very high risk of wildfire, higher than 92 of states in the U.S. When I think of Hawaii, I think tropical not dry, but studies show 90 percent of the state received less rain compared to a century earlier. Which brings me to my last takeaway.

Takeaway 3: The elevated risk of fires is not going away. Climate change is changing our landscape and should be changing how we view these events. According to a study by the UN Environment Program, climate change and land-use change will make wildfires more frequent and intense, with a projected 14 percent increase by 2030 and a 30 percent rise by 2050. These fire risks, and others, such as flooding, are not going away and they will only get worse. If you want to know the fire risk in your area, you can visit the Wildfire Risk to Communities page.

Another trigger of the Maui wildfires was highly ignitable non-native grasses that took over large tracts of land that were once sugar cane plantations. A 2021 fire prevention report by Maui County identified fires as a growing threat due to increasing temperatures, prolonged periods of drought because of climate change, and the impact of intrusive non-native grasses.

As I write this article, I am receiving texts that there is a red flag warning for where I live in the foothills of Colorado. Just to the north of me, the Marshall fire in Colorado, in December of 2021, was fueled by hurricane winds with more than 1,000 homes destroyed. Wildfire season is now year-round in Colorado. I now take these warnings much more seriously and have a mindset to be ready to evacuate at a moment’s notice.

The events in Maui on Aug. 8, 2023, were a worst case scenario. According to researchers, extreme winds with high variability, a fire ignition close to the community, and construction characteristics led to continued fire spread in multiple directions. When you add in the severe drought, the ignitability of the non-native grasses, and limited evacuation routes, it is truly terrifying.

There are signs of hope and positivity in this disaster. There are countless stories of communities pulling together to support each other, grieve with each other, and rebuild together. As we go throughout our daily lives, we all need to be aware and take the warnings from the national weather service and government officials seriously. The worst-case scenario may only happen once out of a hundred warnings we receive, but that worst case scenario can be devastating. For me, the events of August 8, 2023, were a wake-up call — a reminder that being prepared is not just a choice but a necessity.

Maureen Roskoski is a vice president with FEA with 28 years of experience in strategic planning, resilience planning, and workforce development consulting. She is one of Building Operating Management's Facility Influencers.

Maureen is an expert in ISO management systems standards, including the ISO 22301 series on business continuity, the ISO 55000 series on asset management, and the 41000 series on facilities management, and a member U.S. Technical Advisory Group to ISO/TC 267 Facility Management. She supports clients with continuity of operations planning (COOP), organizational assessments, FM technology process improvement, sustainability, and resilience planning.