5 Steps To Emergency Preparedness For Any Disaster

12/12/2022

This article was originally published in 2017 and has been updated to reflect current information.

Whether it’s a fire, flood, shooting, power outage, or other situation, emergencies unfortunately hit the headlines often enough that the subject of preparedness is no longer limited to security and facility professionals. If top management asks what technology, training, or manpower the company should invest in to help ensure that it is prepared for an emergency, that question should not be considered an open invitation to start shopping, but rather an opportunity to discuss, using as much backup data as possible, the needs for each type of emergency.

Getting ready for a discussion like that is one more good reason to think through the activities involved in developing an emergency response plan. (Of course, the biggest reason to pay attention to an emergency response plan is to be as prepared as possible for an emergency.) While there is no one-size-fits-all approach, there are common elements that should be addressed in the creation of a plan. Here are five steps that facility and security managers can use to help guide emergency planning.

1. Know your risks

Listing potential emergencies and ranking them in regards to importance and likelihood is essential to knowing what to do and what resources to invest. There is no need to invest dollars in hurricane planning if your facility is not near a coastal area, nor should you spend a lot of time for earthquake planning if your facility is not near any area normally susceptible to earthquakes or with a history of seismic activity. That doesn’t mean that you totally ignore these risks, just that you don’t dwell on detailed response tasks.

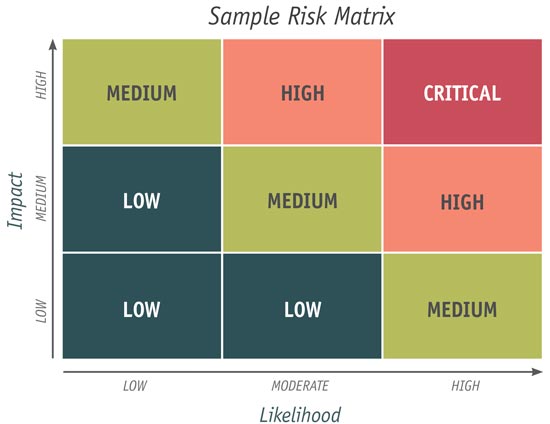

The risk assessment should be based on an all-hazards approach for those hazards affecting the facility. A risk matrix can help identify the areas where an investment is most needed. Using this type of matrix, the facility or security manager can categorize each risk or emergency based on the impact it would have if it occurred and on the likelihood of the event happening in your area. As an example, a critical emergency may be a hurricane in Florida, which would have a high impact on the area and a high likelihood of occurring. On the other end of the spectrum, the risk of the traffic light at the entrance of your facility malfunctioning and causing a traffic backup would have a low likelihood of occurring. Although the latter event does require the use of manpower and other resources, planning to resolve the situation is simple.

Using a risk matrix to evaluate all the potential emergencies your facility may face will give you a head start on many things, including being prepared to meet with management in support of any funding requests for emergency preparedness.

2. Build a team

Many emergency response plans are created in a vacuum, with no input from the end users. That’s the wrong approach to take. In today’s environment, every individual in the organization may have a role as a kind of first responder, who is expected to follow the rule, “see something, say something.” Emergency plans should be the product of an inclusive team instead of a single individual or group.

Putting together a team of subject matter experts from different departments helps in determining the overall span of the plan, including a cycle of the four phases of emergency management:

• Mitigation. Preventing emergencies and minimizing the effects if an event occurs.

• Preparedness. Identified efforts to prepare for the event.

• Response. Plans and efforts to respond safely to the event.

• Recovery. Actions needed to return the facility to normal operations.

Subject matter experts or other representatives from safety, security, human resources, public relations or communications, facilities, operations and upper management should be involved from the start of the planning phase. If plans are already in place, that team would form a good review committee to ensure that all areas are covered.

If a sizable group of a specific type of building occupant — employees, students, or faculty, for example — would be affected by any response plans, it would be wise to have a representative of that group provide input into the process. The people who ultimately are affected by an evacuation or sheltering-in order will tell you that it would be better if everyone involved were told in advance what to do, what process would be used to communicate those orders, and what occupants should expect from security or law enforcement personnel. For example, during an active shooter event, law enforcement personnel will be going to the sounds of the shots to mitigate and end the shooting and will not stop to help others either injured or needing assistance. If building occupants don’t know that this is the correct protocol for police officers to follow, they may come away with a negative impression of the response.

3. Make critical information quickly accessible

So many times, if you ask to see an emergency plan, someone goes to a file cabinet or shelf and pulls out a three ring binder, at least two inches thick, and hands the weighty document to you for reading. A plan like that certainly reflects a lot of work, but does anyone really know what’s in it and does it really describe the methods to respond during the emergency event?

When it comes time to write a plan, the thinking is sometimes that, the bigger the document, the better. This couldn’t be farther from the truth. Plans need to be concise as to the threat, the risk, and then what to do. Long, drawn out supporting documentation that may assist somewhere in the plan as an appendix or supplement is fine, but when users want to know what the emergency is and what to do in that emergency, they want information to be quickly read and easily accessible. Many facilities create a hard copy, full length emergency plan, and then use small “flipcharts” or spiral-bound, hand-size, notepad-type inserts that outline each potential risk or emergency, and then show who to call, with numbers and what occupants should do for their own safety and safety of others.

At Delta Air Lines Technical Operations Center (TOC) in Atlanta, Ga., flipcharts that encompass many emergencies — such as fire/explosion, spill response, severe weather, injury response, emergency disconnects, bomb threat/response along with active shooters — are maintained on the walls of every department for easy access. Obviously, all employees are encouraged to read these in advance to ensure quick response, but in cases of actual events, the flipcharts are available for reference.

Depending on the size and type of organization involved, responsibility for writing the plan, updating it, and normal overall operational control falls either to the safety department, the security department, or in some cases the facilities department.

4. Update your alert and response procedures

Before the days of active shooters, terrorism, and lone offenders and the advent of social media dominating our daily lives, it used to be that an emergency plan consisted of calling 911 and waiting for the police or fire department to arrive, or pulling the fire alarm, evacuating, and waiting for the first responders to arrive. This is no longer the case. Just pulling the fire alarm and evacuating is not the proper response to an active shooter scenario. In fact, it can be dangerous to pull the alarms in case the shooter or shooters are nearby; a better course is to take shelter in an office or other secure area if you are unaware of the shooter(s) whereabouts.

We also live in a world of second-guessing about everything we do or don’t do in an emergency. Plans are made to ensure everyone knows what to do in a timely fashion. Some managers subscribe to the thought that, if it’s not written down, they can’t be held to it. That premise went out the window with the advent of more diverse emergencies and social media broadcasting the emergency details even before the first responders arrive or even know of the event. Plans need to be specific and to the point, with everyone involved knowing what may happen and what to do. This does not mean to put into your action plan the specific details of what the responders will do; rather, the focus in on the plans each person should know to protect her- or himself and others.

Notification tools such as email, voice, and text blasts are now common on college campuses and corporations. However, keep in mind that no one will get the alert notification unless someone starts the process, not only by calling 911, but also by notifying the people responsible for sending out the message to do so. In many cases, the event (shooting or stabbing) has already been concluded before the police arrive, with social media providing reports that are many times erroneous.

In addition, it’s essential that the language of the alerts be clear and easily understood. In November, at the University of Virginia where three football players were killed on a bus after a field trip, an active shooter alert was sent out via social media saying “Run, Hide, Fight,” which is the title of the active shooter video produced by the Department of Homeland Security to train people on what to do in case of an active shooter event. For this alert language to have been well known to all on campus as an indicator to start action, training would have been needed to ensure that everyone actually knew what to do in this case.

The public relations or communications staff needs to be involved in the planning phase, to ensure that concise and authorized language is used in the notifications that are sent. In essence, if the “Run, Hide, Fight” alert was a signal code phrase to begin evacuating or sheltering based on previous and recurring training of all personnel, then it would work.

An after-action report will most likely identify the notification process used and whether it was effective. Although it may be a challenge to add one more thing to do after an event, an after-action report is a valuable tool for evaluating your plan. If you take the time to document all response actions during an event and do an after action report right after, you can glean as much from this as any rehearsed drill you may put on.

5. Test the plan

Once the plan has been created, the next question is, will it work? How do you know? The answer is a series of tests or tabletops, drills, and exercises designed to go through procedures that you are expected to know — in fact, that you need to know to save your own life and the lives of others.

The security or facility manager should already have in place the ability to test the plans to determine if they work or need to be improved, or and to provide continuous tweaking of the plans to ensure any company, facility, or personnel changes are reflected in the plans. Two methods are most cost effective methods: the first is lecture and response sessions and the second is tabletops. Segmented drills, exercises, and full blown drills incorporating many first responder outside agencies are performed after you are comfortable with the results of the lecture and tabletop sessions.

Lectures and response sessions are designed to educate the personnel who need the training on what the risks are and what to do in each emergency; a robust interaction between the lecturer and audience should answer many of the questions that will arise during the session. It’s a good start for any emergency awareness program.

Tabletops are the most accepted means of not only getting the information and response actions in front of the audience, but also giving the participants the ability to actually go through what is needed during the emergency. The tabletop allows participants to simulate the response, not to actually physically perform the actions need.

For example, during an active shooter tabletop, the personnel responsible to sending out an alert message to all in the company would simulate the process by sending out a test message to a select few cell phones of those participating in the tabletop. This not only shows that the system works and how quickly, it also eliminates the need to send out pre-warnings of the content of the message to everyone in the system.

Going through everyone’s responsibilities during the tabletop shows who is responsible and what they do. The most important element is identifying weak links or action items. The tabletop uncovers things that really need be done and by whom; it’s a far better review method than relying on someone who is not really in the loop to look over the plan and offer an opinion on what should be done.

The purpose of drills (beyond ordinary fire drills), and full response and other exercises goes far beyond tabletops and lectures and can bring large costs. A full year is normally needed to coordinate with law enforcement agencies, fire departments and emergency medical services. It costs money for them to participate, to say nothing of your own people’s time. Major drills and full response exercises are great to do, but lectures and tabletops are a cost effective way to continue to educate your personnel on what to do. ■

Robert F. (Bob) Lang, CPP, is retired from from Kennesaw State University as the chief security officer. Before that, he was the director of homeland security and director of research security at Georgia Tech.